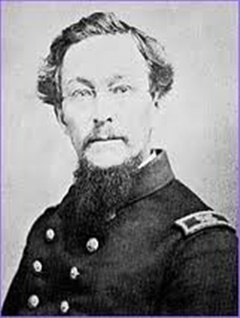

KEELER-WILLIAM

WILLIAM FREDERICK KEELER

UNK

06/09/1821

ACTING PAYMASTER OF USS MONITOR

William Frederick Keeler was born on June 9, 1821, in Utica, New York, the oldest son of a successful businessman. In 1846 he married Anna Dutton and moved to La Salle, Illinois. On December 17, 1861, at the age of 40, Keeler obtained a naval appointment and was given the assignment of Acting Assistant Paymaster and Clerk and sent to New York. The exact date he was assigned to the USS MONITOR is not known but is believed to have been sometime in January 1862. While serving as the paymaster aboard MONITOR, Keeler sent many letters home to his wife. These letters reveal details of life aboard the ironclad and Keeler's opinions of the crew. He was stationed on MONITOR until the ship sank on December 31, 1862. He was not transferred to another ship immediately but spent about a month settling the MONITOR’s accounts. On February 7, 1863, Keeler was stationed on the side wheel steamboat USS FLORIDA, where he remained until the end of the war. Keeler then moved his family to Mayport, Florida. Taking on the assumed title of major, Keeler worked as a customs collector, elections inspector, and railroad paymaster until his death in 1886.

One of Keeler’s letters to his wife is fortunately at the Mariner’s Museum in Newport News and has been eagerly review by historians as it discussed the March 1862 Battle of Hampton Roads, the historic battle between USS MONITOR and CSS VIRGINIA, the first battle between ironclad ships. The following are excerpts from the letter which refers to the CSS VIRGINIA by the Union name of MERRIMAC.

As we neared the land, clouds of smoke could be seen hanging over it in the direction of the Fortress & as we approached still nearer little black spots could occasionally be seen suddenly springing into the air, remaining stationary for a moment or two & then gradually expanding into a large white cloud--these were shells & tended to increase the excitement. We soon took a pilot & then learned that Merrimac was making terrible havoc among the shipping - how slow we seemed to move - the moments were hours. Oh, how we longed to be there-but our iron hull crept slowly on & the monotonous clank, clank, of the engine betokened no increase of its speed. No supper was eaten that night as you may suppose. As we neared the harbor the firing slackened & only an occasional gun lit up the darkness-vessels were leaving like a covey of frightened quails & their lights danced over the water in all directions. We stopped by the Roanoke frigate & rec'd orders to proceed at once to Newport News to protect the Minnesota which was aground there, so we went up & anchored near her.

Everything on board of us had been prepared for action. Kept all hands to quarters through the night. No one slept. The first rays of morning light saw the Minnesota surrounded by tugs into which were being tumbled the bags & hammocks of the men & barrels & bags of provisions, some of which went into the boats & some into the water, which was covered with barrels of rice, whiskey, flour, beans, sugar, which was thrown overboard to lighten the ship. One of the little tugs alongside had the engine & the whole inside blown out by the explosion of a shell in the previous day's fight. After getting up our anchor we steamed slowly along under the towering side of the Minnesota. The men were clambering down into the smaller boats - the guns were being thrown overboard & everything seemed in confusion. Her wooden sides showed terrible traces of the conflict. The announcement of breakfast brought also the news that the Merrimac was coming & our coffee was forgotten.

As the Merrimac approached, we slowly steamed out of the shadow of our towering friend. Every one on board was at his post, except the doctor & myself who having no place assigned us at the immediate working of the ship were making the most of our time in taking a good look at our still distant but approaching foe. A puff of smoke arose from her side & a shell howled over our heads & crashed into the side of the Minnesota. We did not wait but ascended the tower & down the hatchway. As we passed down through the turret the gunners were lifting a 175 lb. shot into the mouth of one of our immense guns. "Send them that with our compliments, my lads," said the Captain. A few straggling rays of light found their way from the top of the tower to the depths below which was dimly lighted by lanterns. Every one was at his post, fixed like a Statue, the most profound silence reigned - if there had been a coward heart there its throb would have been audible, so intense was the stillness.

Soon came the report of a gun, then another & another at short intervals, then a rapid discharge. Then a thundering broadside & the infernal howl (I can't give it a more appropriate name) of the shells as they flew over our vessel was all that broke the silence & made it seem still more terrible. O, what a relief it was, when at the word, the gun over my head thundered out its challenge with a report which jarred our vessel, but it was music to us all. The fight had been opened by the Merrimac firing on the Minnesota who replied by the broadside we first heard. As we lay immediately between the two, we had the full benefit of their shot - the sound of them at least, which if once heard will never be forgotten I assure you. It would not quiet the nerves of an excitable person, I think. Until we fired, the Merrimac had taken no notice of us, confining her attentions to the Minnesota. Our second shot struck her & made the iron scales rattle on her side. She seemed for the first time to be aware of our presence & replied to our solid shot with grape & canister which rattled on our iron decks like hail stones. One of the gunners in the turret could not resist the temptation when the port was open for an instant to run out his head, he drew it in with a broad grin. "Well," says he, "the fools are firing canister at us." The same silence was [again] enforced below that no order might be lost or misunderstood. The vessels were now sufficiently near to make our fire effective & our two heavy pieces were worked as rapidly as possible, every shot telling - the intervals being filled by the howling of the shells around & over us, which was now incessant. The men at the guns had stripped themselves to their waists & were covered with powder & smoke, the perspiration falling from them like rain.

Below, we had no idea of the position of our unseen antagonist except what was made known through the orders of the Captain.

"That was a good shot, went through her water line."

"Don't let the men expose themselves, they are firing at us with rifles."

"She's too far off now, reserve your fire till you're sure."

"They're going to board us, put in a round of canister."

"Can't do it," replies Mr. Green, "both guns have solid shot."

"Give them to her then."

"Why don't you fire?"

"Can't do it, the cartridge is not rammed home."

"Depress the gun & let the shot roll overboard."

"It won't do it."

"How long will it take to get the shot out of that gun?"

"Can't tell, perhaps 15 minutes."

And we hauled off, as the papers say, "to let our guns cool."

We were soon ready for her again as the order from Captain indicated - "Look out now they're going to run us down, give them both guns." This was the critical moment, one that I had feared from the beginning of the fight - if she could easily pierce the heavy oak beams of Cumberland, she surely could go through the 1/2 inch iron plates of our lower hull. A moment of terrible suspense, a heavy jar nearly throwing us from our feet - a rapid glance to detect the expected gush of water - she had failed to reach us below the water & we were safe. The sounds of the conflict at this time were terrible. The rapid firing of our own guns amid the clouds of smoke, the howling of the Minnesota's shells, which was firing whole broadsides at a time just over our heads (two of her shot struck us), mingled with the crash of solid shot against our sides & the bursting of shells all around us. Two men had been sent down from the turret, who were knocked senseless by balls striking the outside of the turret while they happened to be in contact with the inside.

At this time a heavy shell struck the pilot house - I was standing near, heard the report which was unusually heavy, a flash of light & a cloud of smoke filled the house. I noticed the Captain stagger & put his hands to his eyes - "My eyes," says he, "I am blind." Blood was running from his face, which was blackened with the powder smoke. The quartermaster at the wheel, as soon as the Captain was hurt, had turned from our antagonist & we were now some distance from her. We held a hurried consultation & "fight" was the unanimous voice of all. Lieut. Greene took the Captain's position & our bow was again pointed for the Merrimac. As we neared her she seemed inclined to haul off & after a few more guns on each side, Mr. Greene gave the order to stop firing as she was out of range & hauling off. We did not pursue as we were anxious to have more done for the Captain than could be done aboard.

Our iron hatches were slide back & we sprang out on deck which was strewn with fragments of the fight. Our foe gave us a shell as a parting fire which struck just over our heads & exploded about 100 feet beyond us. In a few minutes we were surrounded by small steamers & boats from Newport News, the Fortress, the various men of war, all eager to learn the extent of our injuries & congratulate us on our victory. They told us of the intense anxiety with which the conflict was witnessed by thousands of spectators from the shipping & from the shore & their astonishment was no less on learning that though we were somewhat marked we were uninjured & ready to open fire again. The battle commenced at 1/2 past 8 A.M. & we fired the last gun 10 minutes past 12 (P). Captain was taken off in a tug boat. Our Stewards went immediately to work & at our usual dinner hour meal was on the table, much to the astonishment of visitors who came expecting to see a list of killed & wounded & a disabled vessel, instead of which was a merry party around the table enjoying some good beef steak, green peas, &c.

Submitted by CDR Roy A. Mosteller, USNR (Ret)