Excerpts from article published in San Diego Union Tribune on 6/5/2019:

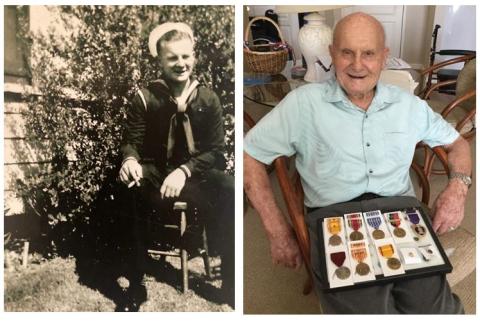

74 YEARS LATER, VET HONORED

Pearl Harbor veteran George Coburn waited nearly 75 years for the service medals he earned during World War II. On June 4, a grateful nation finally paid its debt to the 99-year-old retiree. In a brief ceremony a U.S. Representative paid tribute to Coburn’s service and bravery while awarding him eight medals for his service in the Navy from 1938 to 1946. Coburn said that when the war ended “things got a little screwy because everyone was so busy celebrating.” Although the Navy did present him with a Purple Heart in 1945 for injuries sustained during the Battle of Okinawa, paperwork for his other service honors was never processed. While joking during the presentation ceremony he said, “People always say to me ‘thank you for your service.’ I tell them I did it willingly, but I can’t say it was enjoyable and don’t ask me to do it again.” The Representative’s staff spent months working with the Navy to obtain Coburn’s long overdue medals after learning from a World War II historian that Coburn had never received his medals.

Colburn was a baby when his family moved to San Diego in 1920. After graduating from high school, he got a job selling used cars for 25-cents an hour, but the pay wasn’t steady, so he enlisted in the Navy on February 11, 1938. Coburn was a fire controlman first class on the battleship Oklahoma when the Pearl Harbor attack began on December 7, 1941. As general quarters sounded, he and dozens of others struggled to comply. When a series of torpedoes hit the ship, it quickly listed on its side and the men became trapped under a sealed hatch. The lights went out and Coburn could hear water pouring into the ship. Men on a ladder frantically tried to open the hatch to the deck above and one of the anchors holding the ladder in place broke. “Panic was growing,” he said. Eventually the hatch was opened, and the ladder held long enough for the men to climb up, and finally to the main deck. The ship was beginning to roll upside down, so Coburn and a handful of men pulled themselves up through a side porthole, which was overhead, to stand on the bottom of the inverted ship. To avoid being shot by Japanese airplanes, he leapt into the bay as bullets rained down in the water. To escape approaching flaming oil, he grabbed a mooring line hanging from the battleship Maryland and hauled himself up the rope to its deck and spend the rest of the raid handling ammunition for anti-aircraft guns.

Ten days later, Coburn was assigned to the cruiser Louisville on which he served until the end of the war. One of his last major conflicts was during the Battle of Okinawa when a Japanese kamikaze pilot dived bombed the Louisville. Coburn doesn’t remember the impact because he was knocked out in the blast and injured by shrapnel. “I remember that as I stepped out on the weather deck to go to my battle station, I saw a plane heading toward us. Our guys were all firing at him, and they were hitting him. Pieces of the plane were falling off into the water. I thought, ‘Well, he’s not going to make it.’ But he did.”

Coburn met his wife at a Thanksgiving dinner, while on shore leave in Vallejo in 1945. They married in May 1946, five days after his discharge from the Navy at the rank of Lieutenant Junior Grade. They had two children and enjoyed 60-years together before she died in December 2005. After the war, Coburn worked as a civilian Navy contractor and an electrician. He didn’t attend Pearl Harbor reunions or participate in veterans service organizations because he wasn’t a joiner. “Of course, I remember everything about the war, but I just try not to think about it anymore. I preferred to move on and go my own way,” he said

Submitted by CDR Roy A. Mosteller, USNR (Ret)