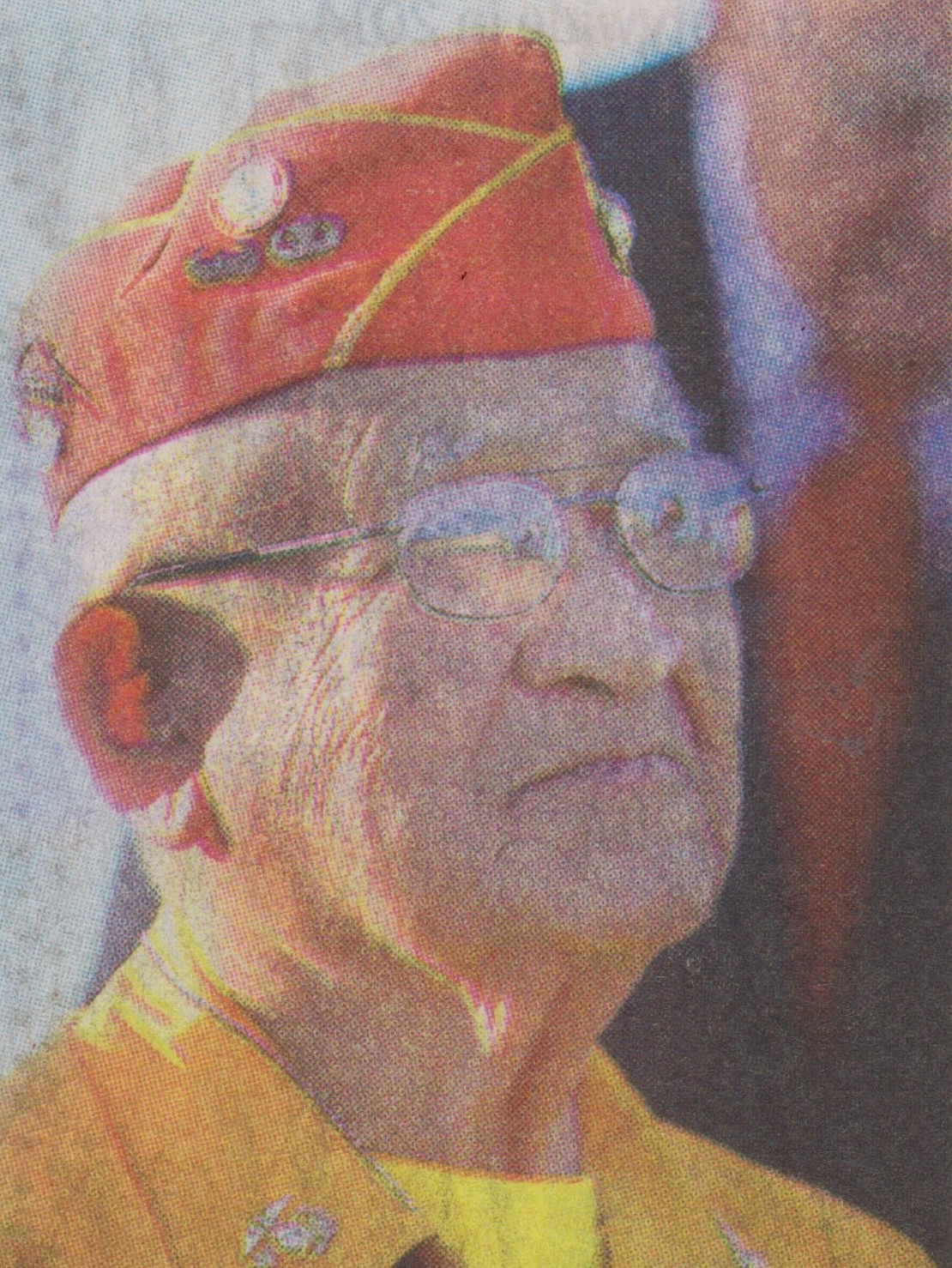

BEGAY-THOMAS

THOMAS H. BEGAY

PFC

CAREER AS MARINE CODE TALKER THEN AS ARMY PARATROOPER

Thomas H. Begay, a member of the Navajo Nation, spoke only the Navajo language until he was 13 when he was sent to an Indian boarding school where he was forced to speak only English. During the early stages of World War II a group of Navajos were recruited into the Marine Corps where they developed a spoken code and formed the Navajo Code Talkers who were instrumental in helping to win victory over the Japanese in the Pacific theater. The Navajo code talkers became so successful that recruiters were sent to Navajo boarding schools to recruit additional Navajos who were fluent in their native language. In 1942 a recruiter arrived at Begay’s school and although he was only age 15, he managed to successfully join the Marine Corps. Begay expected to be placed in gunnery school but was told he would become a code talker. Although he protested he was sent to Camp Pendleton where he found himself surrounded by fellow Navajos, all of whom were learning to be code talkers. They were taught how to use radios, Morse code and learned the difficult code. At the time the program was highly classified and Begay later recalled, “If you talk about what this school is about to anyone, the Marine Corps will put you before a firing squad! They might have said that just to scare us, and they might not have meant it, but we definitely believed them!”

On February 19, 1945, Begay was aboard a ship off the coast of Iwo Jima as the Marine invasion began. He said, “I couldn’t believe how ugly and forbidding that place looked. It made me very uncomfortable and then something happened that confirmed that feeling. Another code talker and I had our radio net operating when a shell, fired from the island, bounced off just below where we were standing. It bounced off the next deck below and exploded on the third bounce. We would have been the first casualties of Iwo Jima if that shell had exploded on impact. Things like that made you glad that you performed your ceremony.” When a code talker was killed on the island, Begay was sent ashore to replace him and he was one of the code talkers who reportedly sent and received more than 800 messages during the battle after which a senior Marine officer has been widely quoted as saying, “We could not have won Iwo Jima without the Code Talkers.” Begay continued his service on Iwo Jima after the battle and recalled that he and a fellow code talker were near the airfield when they smelled cooking. “Fresh food, you could smell it anywhere! You could smell the death, too. We made up an excuse that our radio battery had run down and we needed to go back to headquarters for a new one. We took off and just about 100 yards away a signal company had hot chow cooking. I grabbed my mess kit and joined the line. For days all we had were C rations, so we jumped at the chance for hot, fresh food.” Concerning his service on Iwo Jima he said, “We were disciplined. I learned to survive combat. The first hour, I was with my radio, communication with other floats. I was scared. Mortars and artillery were landing everywhere but I wasn’t hit. The Iwo Jima sand was ashy and hard to walk on, but I had to carry my radio and other equipment across it.”

Following his Marine Corps service, Begay returned to his home but when he could not find work he joined the Army in 1946. He became a paratrooper and radio operator, and found himself in the war zones of the Korean War in 1950, including the long winter battle of the Chosin Reservoir. He was one of the last soldiers to be evacuated as the Allies left the region. Throughout his military experience, he said, the one mission he was always aware of was to “Stay alive and keep your biddies alive. I was awarded six battle stars during my military career for being in major battles from Iwo Jima to Korea. I was never wounded or shot but was missed by inches, and missed being captured by thirty minutes or less. I was very lucky to have gotten through that time. Maybe because I believe in the traditional Navajo ways and felt the Great Spirit was protecting me. My parents, both very traditional Navajos, had ceremonies for me using clothes that I had worn before I left home to go in the service. These ceremonies protected my well-being, so I could survive.” Following his Army service, Begay enjoyed a long career with the federal Bureau of Indian Affairs, where he retired in 1984.

In March 2015, a ceremony was held at Marine Corps Base Camp Pendleton, a somber commemoration of the bravery and sacrifice of the troops who faced that horrific fight 70-years previously on Iwo Jima. Begay was present as an honored veteran of the battle and told how he remembered almost passing out from the smells, the sick smells of ailing and dying men. He also remembers shivering in the cold, possibly with “a touch of malaria.” But he said in an interview after the ceremony, “Survival is one of the things you have to learn. To protect yourself, avoid getting hit by the enemy. You gotta be quick.” His oldest son, an Army veteran who traveled with him to Camp Pendleton, said he was very proud of his father. “He’s definitely a hero to all of us.”

Submitted by CDR Roy A. Mosteller, USNR (Ret)