BOGGS-CECIL

CECIL GUY BOGGS

LCDR

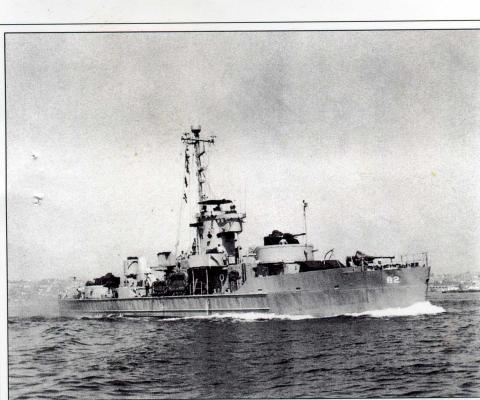

The USS Essex (CV-9) with Air Group Nine (fighter, dive bomber and torpedo squadrons) aboard was anchored in the New Hebrides Islands in November 1943. I was awakened by the ship’s unexpected movement. We were underway, headed “up the slot” between New Guinea and the Solomon Islands. Our destination was Rabaul Harbor to attack Japanese Naval forces posing a threat to our Marines who had recently established a beachhead on Bougainville.

During the early morning on Armistice Day 1943, our air group was launched and headed for the target. Japanese planes intercepted us but didn’t get too close until we began our attack. Mine and my wingman’s assigned target was a cruiser docked at the furthermost part of the harbor. Japanese fighters began attacking us as we pushed over into our dive from about 15,000 to 18,000 feet. About half way down, while in an almost vertical position, I fired my two 50 caliber guns at the cruiser from bow to stern several times before dropping my bomb. I pulled out of my dive so low that I was no more than 50 feet off the water and between two Japanese Naval vessels. They would have been shooting at each other if they hadn’t waited until I was almost to the harbor entrance. Zeroes were now making their runs at me. I saw a small cloud reaching to the harbor entrance and pulled up into the bottom of it so I could see the water but the Japanese fighters could not see me. I ran out of cloud cover and spotted my wingman under attack by about 8 fighters. I signaled him to join up so that we could concentrate our firepower, but it was too late. His plane was in flames 50 to 100 feet above the water. He hit the water in flames.

The Japanese then concentrated on me. I flew so close to the water as I dared, using every evasive tactic I knew, while using language that I didn’t learn in college to tell the gunner where the attacking planes were coming from – and giving our own fighters hell for not being there to cover my retreat. My gunner was not answering me, nor were his guns busy. I assumed he was busy or a casualty. I kept talking to him anyway and when a Japanese plane came by after firing at me, I would pull up and fire at him as he went by. At least two of them headed toward the beach leaving a trail of smoke. By this time I was clear and out into the Coral Sea, my plane full of bullet holes and practically no fuel. My gunner was okay.

I made an emergency landing aboard and was promptly called to the bridge. I reported immediately, thinking I was to be complimented for a successful flight. The greeting I received was friendly but stern, “Lt. Boggs, we appreciate your narration of your flight. It kept us well informed as to what was happening. But next time, turn your radio to intercom to talk with your gunman (I had been broadcasting my actions and describing the enemy in that non-collegiate language).”

Later that day we were launching a second attack when the Japanese attacked our carrier force. That group was almost completely annihilated. Our loss was limited to one bomber and one fighter. Our air group alone shot down 62 enemy planes and damaged many ships. After this attack our carrier force was retreating and I was rewarded with an assignment to single plane “picket patrol” between our force and the Japanese, flying back and forth perpendicular to our force track to spot enemy planes or ships on our tail. I landed aboard after sundown after having difficulty getting my wheels down. However, back safely and ready for another day.

NOTE: LCDR Boggs was given a Naval Intelligence assignment with the Office of Naval Intelligence in 1951 and transitioned to civilian employment in 1954 as a Special Agent with the ONI organization which has since become the Naval Criminal Investigative Service (NCIS). He served in a number or NCIS locations and upon retirement was the Assistant Supervising Agent at the Naval Investigative Service Office, Washington. He died at the age of 97 on March 29, 2016, and has been laid to eternal rest at the Florida National Cemetery.