KENNETH R. WILLIAMS

MORRISTOWN, NJ

Robert Byron Fuller

Date of birth: November 23, 1927Place of Birth: Mississippi, Quitman

Home of record: Jacksonville Florida

Status: POW

Robert Fuller graduated from the U.S. Naval Academy at Annapolis, Class of 1951. He was interned as a Prisoner of War in North Vietnam after he was shot down on July 14, 1967, and was held until his release on March 4, 1973. He retired as a U.S. Navy Rear Admiral.

AWARDS AND CITATIONS

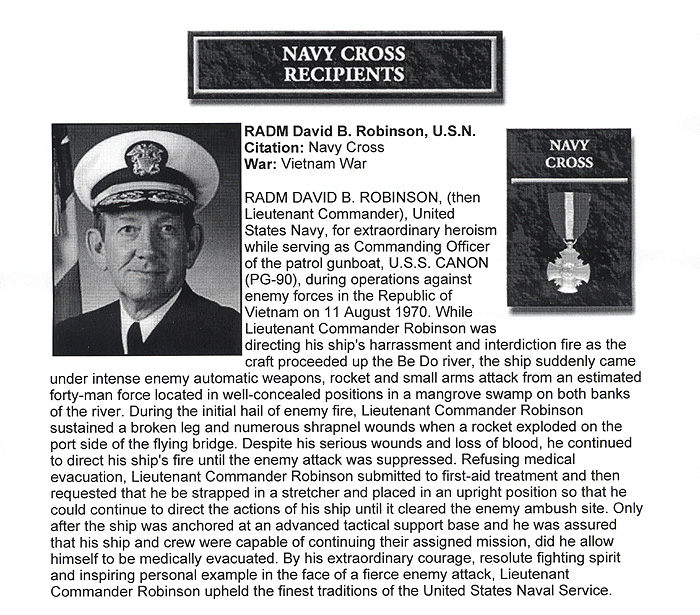

Navy Cross

Awarded for actions during the Vietnam War

The President of the United States of America takes pleasure in presenting the Navy Cross to Captain Robert Byron Fuller (NSN: 0-542942), United States Navy, for extraordinary heroism as a Prisoner of War (POW) in North Vietnam during the month of October 1967. During this period, as a prisoner at Hoa Lo POW Prison, he was subjected to severe treatment at the hands of his North Vietnamese captors. As they persisted in their harsh treatment of him, he continued in his refusal to give out biographical data demanded by the North Vietnamese. He heroically resisted all attempts by his captors to break his resistance indicating his willingness to suffer any deprivation and torture to uphold the Code of Conduct. Through those means, he inspired other POW's to resist the enemy's efforts to demoralize and exploit them. By his gallantry and loyal devotion to duty, he reflected great credit upon himself and upheld the highest traditions of the Naval Service and the United States Armed Forces.

General Orders: Authority: Navy Department Board of Decorations and Medals

Action Date: Oct-67

Service: Navy

Rank: Captain

Division: Prisoner of War (North Vietnam)

Submitted by Doug Bewall RMCM USN Ret

75363

75453

75453  75663

75663

75722

75722  75760

75760  75839

75839  75852

75852  75925

75925

76000

76000

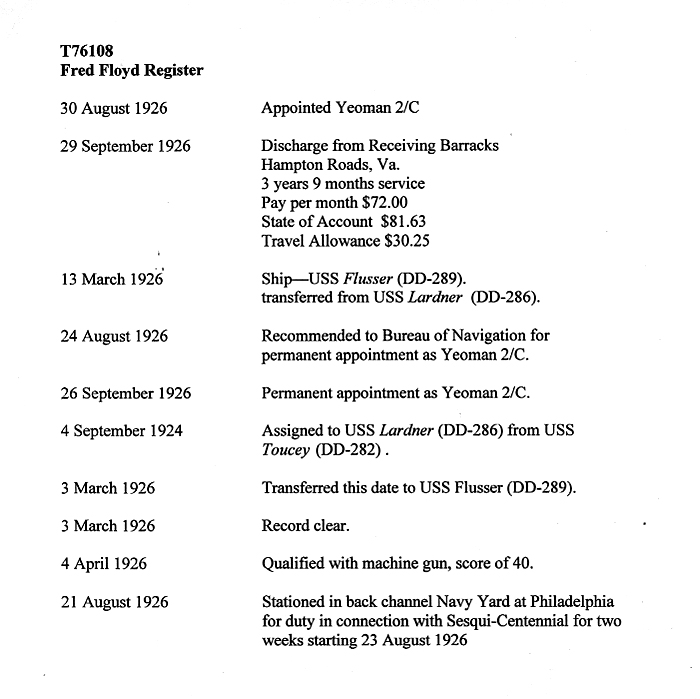

76108

76160

76160

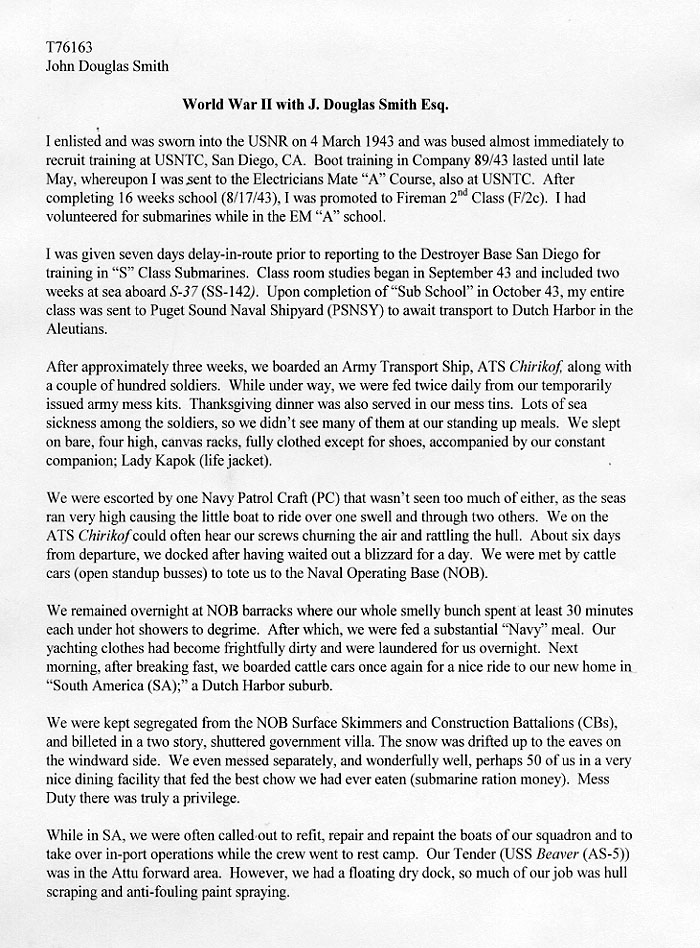

76163

76163

76165

76165

76212

76212  76232

76232  76405

76405

Cold War Victory medal

76464

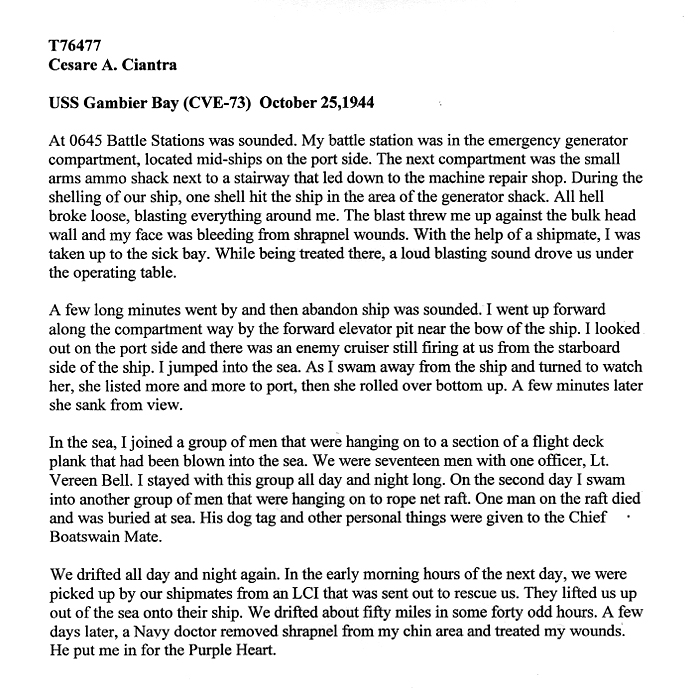

76464  76477

76477  76494

76494

76495

76495  76563

76563

76636

76636  76730

76730  76812

76812  76851

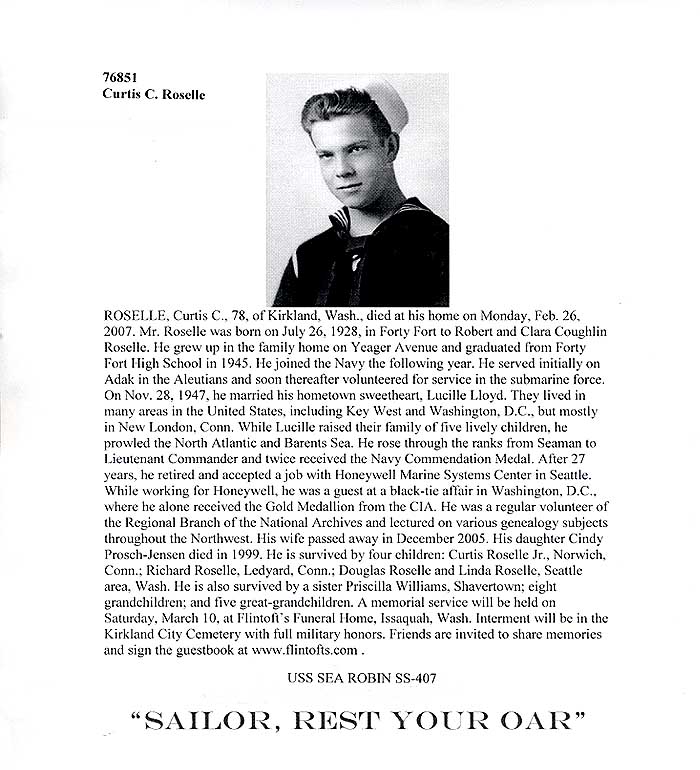

76851

76936

76936  76998

76998  77060

77060

77189

77189  77268

77268 Trumpet/Post Horn Soloist US Navy Band

77286

77308

77308  77334

77334  77348

77348

77398

77398

77504

77504

77586

77586  77614

77614  77673

77673 WAVES MEMBER TURNS 100

Article published in June 2012 issue of MILITARY OFFICER MAGAZINE, a monthly publication of the Military Officers Of America:

Kathryn Barclay joined the US Navy in Canton, Illinois, in 1942. On February 9th, as she turned 100 years old, she still remembers fondly her service in the military and her proudest accomplishments. Barclay, who retired as a Lieutenant Commander, was one of the first women to serve with the Women Accepted for Volunteer Emergency Service (WAVES). She served in the Navy as a nurse during World War II and the Korean War. I worked setting up the operating rooms, Barclay says. They wouldn't even go in there until I was there. One time I even got to perform an appendectomy. I was always in the operating room.

Submitted by CDR Roy A. Mosteller, USNR (Ret)

77721

77721  77728

77728  77815

77815  77879

77879  77881

77881  77912

77912  77935

77935  77983

77983

78030

78030

78276

78276  78290

78290

78366

78366

78452

78452  78480

78480

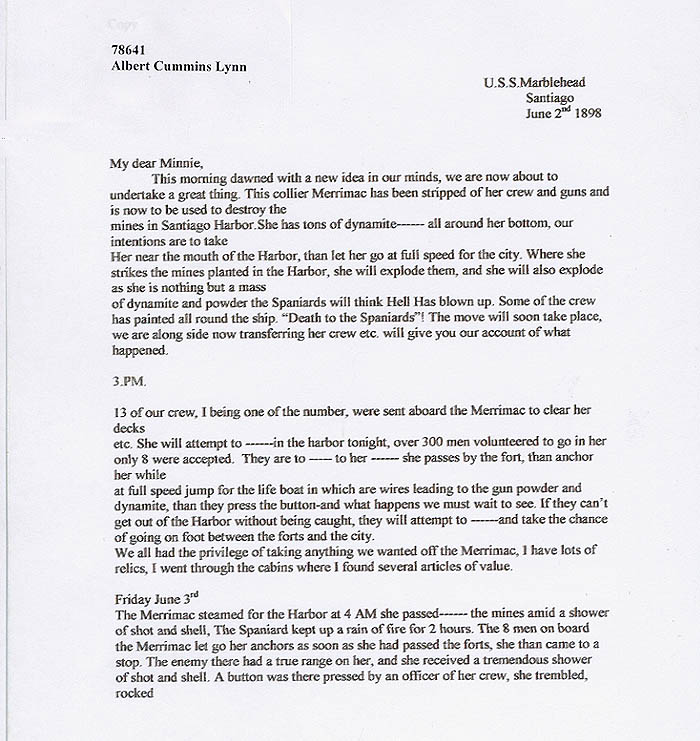

78641

78641

78782

78782

78882

78882

78973

78973  78995

78995  79008

79008

79024

79024

79054

79054  79059

79059  79096

79096  79120

79120  79165

79165  79181

79181  79251

79251

79465

79465 ADDITIONAL ITEMS FOR SERVICE MEMORIES:

USS ESSEX CVS-9, CREW MEMBER FOR APOLLO 7 MISSION RECOVERY SHIP AND CREW MEMBER FOR THE DECOMMISSIONING OF THE ESSEX.

TRANSFER CREW MEMBER OF YOSEMITE AD-19 FROM NEWPORT, RI TO MAYPORT, FL.

ADDITIONAL DUTY AS FORENSIC DENTIST, 1973-1992.

79603 79605

79605  79671

79671  79709

79709

HE HELPED TO CAPTURE A GERMAN U-BOAT

On June 4, 1944, an incident without historical precedent since 1815 occurred about 150-miles off the west coast of Africa - the boarding and capture during battle of an enemy warship on the high seas by the US Navy. Phillip N. Trusheim was the coxswain of the whaleboat from the USS PILLSBURY (DE-133) which managed to board and capture the German submarine U-505 in this unique event.

In a 2004 interview, Trusheim said that he enlisted in the Navy in 1941 and was stationed at the Naval Air Station at Kaneohe Bay, Hawaii, when the Japanese attack Pearl Harbor. He remembers that he was very scared as he watched Japanese bombs fall around him that Sunday morning. Less than a month later he was assigned to the USS WRIGHT (AV-1), a supply ship that delivered supplies throughout the South Pacific during the early days of WWII. In early 1943 he was transferred to the USS PILLSBURY, a destroyer escort commissioned in June 1943. In June 1944, PILLSBURY was escorting the escort aircraft carrier USS GUADALCANAL (CVE-60) as a member of antisubmarine hunter-killer Task Group 22.3 which had sailed from Norfolk on May 15, 1944, on its third mission. During its first two forays in January and April, Task Group 22.3 had badly damaged one German U-boat and sunk three others. CAPT Daniel V. Gallery, the task group commander aboard GUADALCANAL formed an audacious plan to force a damaged German U-boat to the surface, force its crew overboard, and then board and capture it before it sank. On May 17, 1944, CAPT Gallery sent a message to his escort ships: EACH ESCORT DRAW UP PLANS AND ORGANIZE A PARTY TO BOARD-CAPTURE AND TAKE SUB IN TOW IF OPPORTUNITY ARISES. CAPT Gallery later exclaimed, The plan worked to perfection! During an interview in 2004, Trusheim remarked that although he thought the plan to capture a German submarine was Nuts when he first heard about it, he volunteered and was assigned duty as coxswain of the PILLSBURY boarding party whaleboat.

Until the bright and sunny morning of Sunday, June 4, 1944, the passage of Task Group 22.3 had been uneventful and with fuel running low CAPT Gallery had ordered them to make for Casablanca to refuel. At 1109 one of the escorts reported, WE ARE INVESTIGATING POSSIBLE SOUND CONTACT. At 1112, the escort signaled her confirmation of the contact as a submarine, later identified as the U-505, and fired a full pattern of hedgehogs at the submerged contact. The contact-detonated hedgehogs missed their target. Two Wildcat fighter planes from GUADALCANAL, which had been providing air cover, immediately commenced searching, quickly sighted the submerged U-boat and marked its location by firing into the water directly over it. A second depth charge attack brought the damaged submarine to the surface where it found itself in the worst possible location as it was surrounded by TG 22.3 ships which commenced a heavy barrage of antipersonnel fire designed to force the crew overboard without causing serious structural damage.

At the orders of their commanding officer, the U-505 crew opened scuttling valves, set demolition charges and quickly dove overboard from the sinking U-boat. Seeing the crew abandoning the U-boat, an order not heard aboard a U.S. Navy ship in over 100-years was sounded - Away all boarding parties. The PILLSBURY whaleboat, with Trusheim at the tiller, commenced chasing the obviously sinking submarine which was moving at about 6-knots in a tight circle to the right with its rudder jammed from the depth charges, afterdeck completely submerged, the bow high and the conning tower barely awash. Trusheim said it took him about 10 to 10 minutes to reach the U-505 which he did by cutting across its circling path. He ran his boat up the U-505's starboard side hoping that the pressure of the U-boat bearing to the right would aid him in butting the whaleboat up against the conning tower rail. On reaching the U-505 the boarders managed to snag a railing with a boat hook and the boarders struggled to scramble aboard. One member of the boarding party was not so fortunate and was seriously crushed when he fell between the whaleboat and conning tower, thus becoming the only American casualty of the operation.

Once the boarding party was aboard the rapidly sinking U-505 they found that all of the crew had abandoned ship so they quickly set about their assigned duties of stopping the flow of water into the U-boat, locating and disarming explosive charges, and retrieving documents and equipment of very significant intelligence value. Their herculean efforts were rewarded as they managed to keep U-505 afloat, eventually stop its engines, restore electricity and air pressure and pump out the water. The boarding party raced against time to perform the numerous superman tasks to keep their prize intact. They took over the U-505 in a foundering condition, with water pouring in from all sides. Most of the men had never set foot on a submarine but they managed to check the flow of water just a hair short of sinking. If the U-505 had gone down it would have undoubtedly taken the boarders with her as the conning tower hatch had been closed to stop the flow of water as waves washed over the rapidly sinking U-boat. As members of the boarding party struggled below, Trusheim continued to man the whaleboat and made trips to the PILLSBURY to return the seriously injured man for medical aid, and to obtain tools and equipment needed to keep the U-505 afloat. During his 2004 interview Trusheim was asked if he had been scared during this action and he replied that he was too busy to be scared and that he had not been nearly as frightened as he was on December 7th when watching Japanese bombs drop near him at Kaneohe Bay.

The Commander in Chief, US Atlantic Fleet, later remarked, The Task Group's brilliant achievement in disabling, capturing and towing to a United States base a modern enemy man-of-war in combat on the high seas is a feat unprecedented in individual and group bravery, execution, and accomplishment in the Naval History of the United States.

The whole Task Group 22.3 was awarded the Presidential Unit Citation. The members of the PILLSBURY's boarding party, including Phillip Trusheim, were awarded the Silver Star for their heroic actions.

Submitted by CDR Roy A. Mosteller, USNR (Ret)

83256Excerpts from obituary published in San Diego Union-Tribune on 10/10/2013:

The family of Captain Richard Francis Schillaci, MD, was saddened by his passing on September 25, 2013. CAPT Schillaci was a native of Baltimore, Maryland, a graduate of Johns Hopkins University and the University Of Maryland Medical School. His specialty training included Deep Sea Diving School in Washington, DC, and Submarine Medical School in Groton, Connecticut. He served as Medical Officer on the USS SAM HOUSTON, the USS ULYSSES S. GRANT and was an instructor at the Naval Submarine Medical Center before leaving the submarine service. He completed his Internal Medical Residency at St. Albans Hospital in New York. The family moved west in 1968 when he joined the internal medicine staff as head of the Pulmonary Disease Section at the Naval Hospital Oakland, California. He fulfilled his last post at the Naval Hospital San Diego where he served as Head of the Pulmonary Division and Director of Training. His numerous professional affiliations include: Fellow, American College of Chest Physicians; Fellow, American College of Physicians; American Thoracic Society; Association of Military Surgeons; Undersea Medical Society; Naval School of Health Sciences; Specialty Advisor to the Naval Medical Command, Washington, DC. He shared his life journey with his beloved wife Patricia (deceased 2004) and his two daughters. CAPT Schillaci is survived by his daughters, his mother, and sister. He will be greatly missed. In accordance with his wishes there will be no public memorial service and he will have a military burial at sea with full honors. Donations may be made in his honor to the American Cancer Society and the Wounded Warrior Project.

Submitted by CDR Roy A. Mosteller, USNR (Ret)

83274 83385

83385

83481

83481

83677

83677

83687

83687  83727

83727  83731

83731

83733

83750

83750  83775

83775  83790

83790

83849

83849

83869

83869  83906

83906  84052

84052  84103

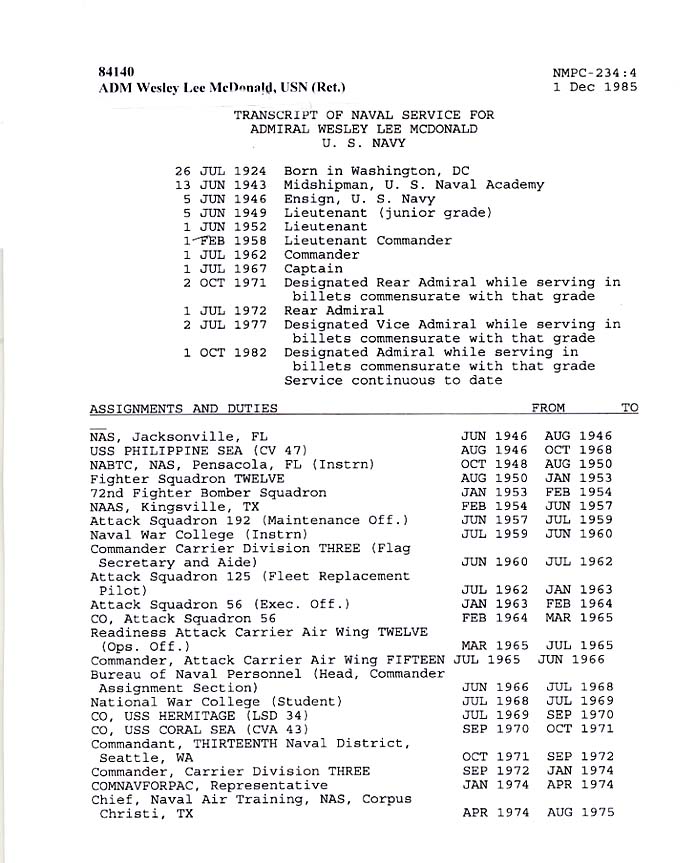

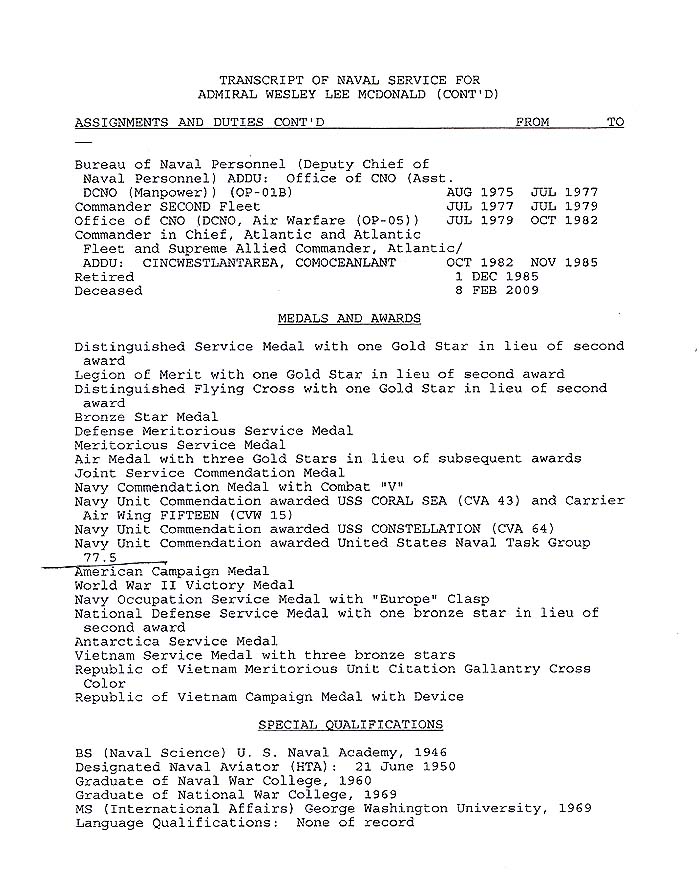

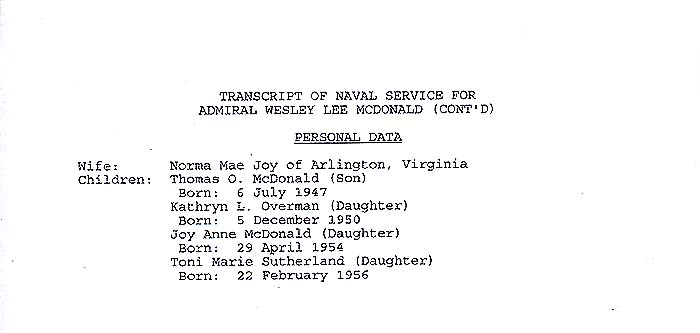

84103  84140

84140

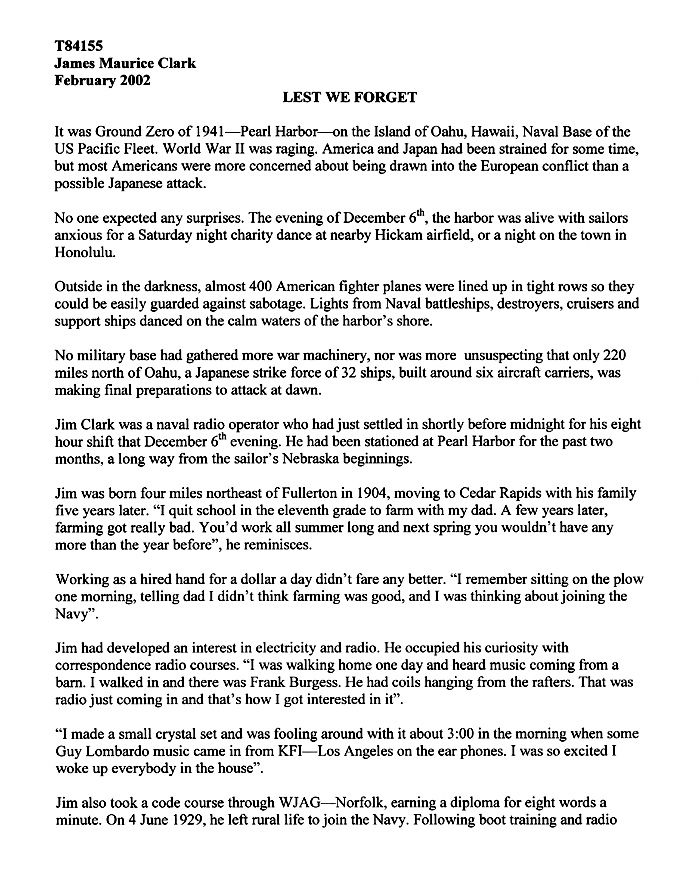

84155

84155

84305

84305  84391

84391  84446

84446 EISELE, GEORGE RAYMOND

Citation:

The President of the United States takes pride in presenting the Navy Cross (Posthumously) to George Raymond Eisele, Seaman Second Class, U.S. Navy (Reserve), for extraordinary heroism and devotion to duty in action against the enemy while serving as a Gunner aboard the Heavy Cruiser U.S.S. SAN FRANCISCO (CA-38), during an engagement with Japanese naval forces near Savo Island in the Solomons on the night of on November 12 and 13 1942. Courageously refusing to abandon his gun in the face of an onrushing Japanese Torpedo Plane, Seaman Second Class Eisele, with cool determination and utter disregard for his own personal safety, kept blazing away until the hostile craft plunged out of the sky in a flaming dive and crashed on his station. His grim perseverance and relentless devotion to duty in the face of certain death were in keeping with the highest traditions of the United States Naval Service. He gallantly gave up his own life in the defense of his country.

Submitted by Doug Bewall RMCM USN Ret

84640

84640

84786

84786

84788

84788

84788 Marjorie Herbert Theriot

My Service Memories

I have a solemn duty to the United States Navy and my beloved country to document my service in World War II.

I was discharged on 13 March 1946, and I am proud to have served in our Navy.

I was first in my 16-week class to master the Top Secret Japanese code, taught at the U. S. Navy Advanced Radio Station on Bainbridge Island, Washington. My duty was to intercept messages that Radio Tokyo sent to all their ships at sea and island stronghold in the Pacific.

The U.S. Navy was diligent in its strategic attacks and maneuvers so as not to reveal we had broken the Code Purple.

A page inserted in my records stamped November 17,1945, imperial Beach Radio Station, to be shown to all future employers, states that I.held a position of special trust under oath of secrecy and no attempt be made to extract further information.

It was not until 1995,50 years after signing of the Peace Treaty with Japan, that President Clinton announced the declassification of many of World War ll's Top Secret documents. It was only then that I was able to reveal to family and friends the nature of my duties as a Radioman in the United States Navy.

My service as a Navy WAVE was the most challenging and rewarding experience of my youthful years before my later life as wife and mother. Today, I still have that intense feeling of patriotism, and I am proud to have served my beloved country in World War II.

Respectfully submitted, Marjorie Herbert Theriot May 24, 2012

84789

84915

84915

84962

84962

85075

85075  85108

85108  85110

85110  85123

85123

85296

85296

85336

85336  85361

85361  85506

85506  85533

85533  85544

85544  85560

85560  85671

85671

85751

85751  85947

85947  86156

86156  86173

86173

86212

86212  86284

86284 Excerpts from obituary published in San Diego Union-Tribune on April 29, 2012:

Jerry Tingle was born on October 26, 1929, in Fort Worth, Texas. At the early age of 16 he joined the Navy during January 1946 and was sent to San Diego for basic training. Here he began a long Navy career lasting until September 1975 when he retired with the rank of Chief Warrant Officer-W3. He had settled with his family in San Diego and having a passion for golf, was well known for coordinating tournaments on the military courses in San Diego. He helped organize and run the Retired Old Duffers, RODS, a golfing group still going strong at the time of his passing. He will be remembered for his passion for life and for his generosity to so many. Jerry died on April 14, 2012, and will be laid to rest at Fort Rosecrans National Cemetery in San Diego.

Submitted by CDR Roy A. Mosteller, USNR (Ret)

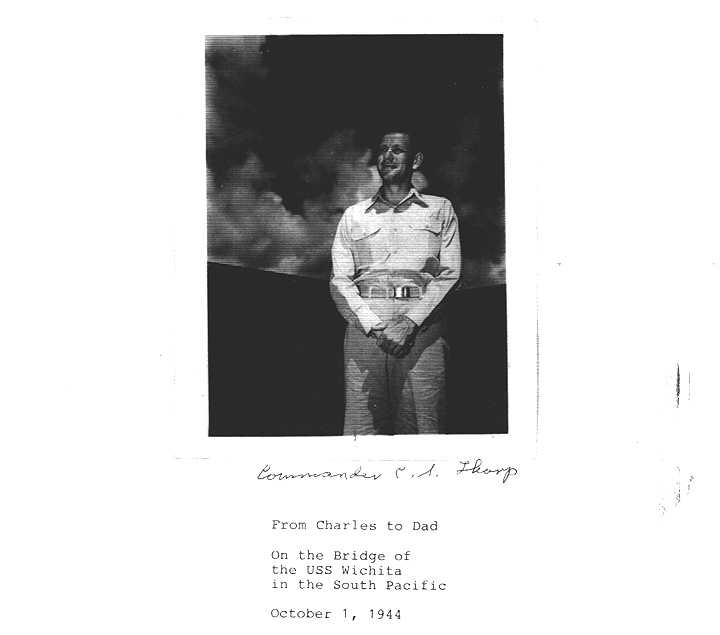

86497

My father was a proud sailor! His service inspired four brothers, two sons and a grandson to follow his footsteps. Thank you Dad for leading the way.....fair winds and following seas......Sailor rest your oar!

86500 86636

86636

86707

86707

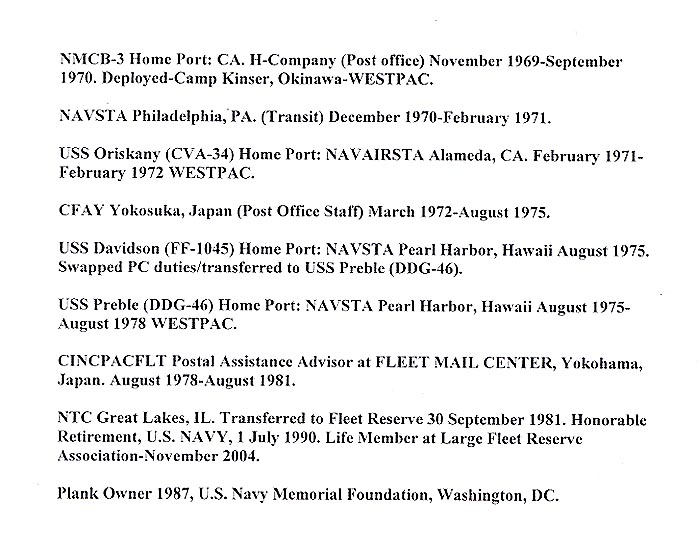

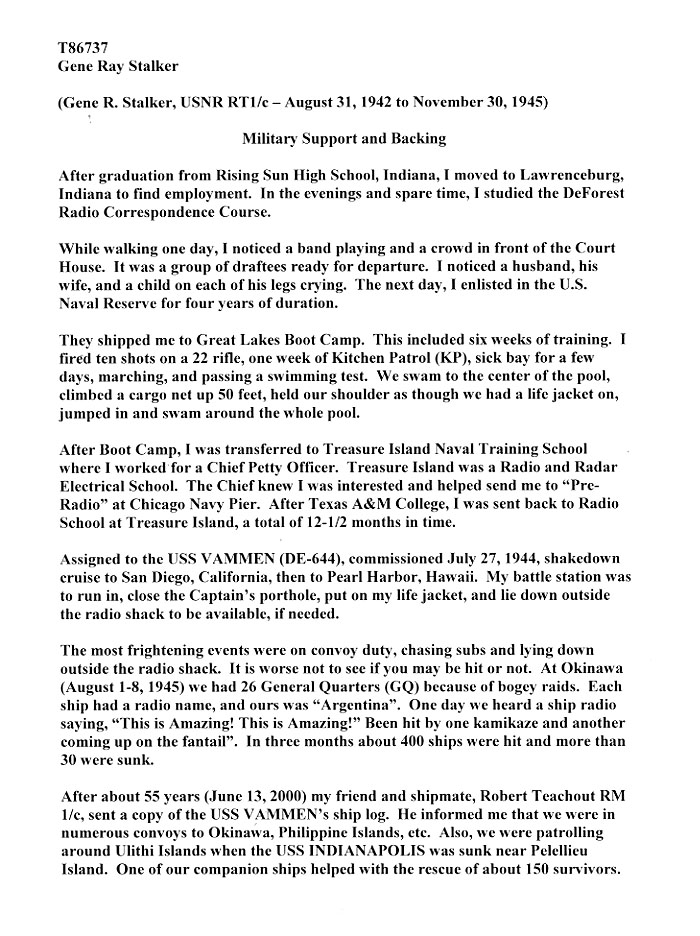

86737

86737

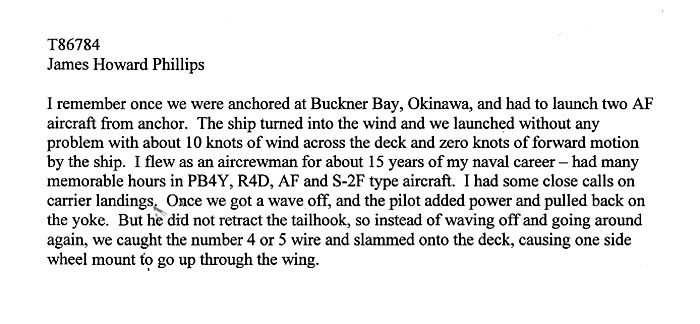

86784

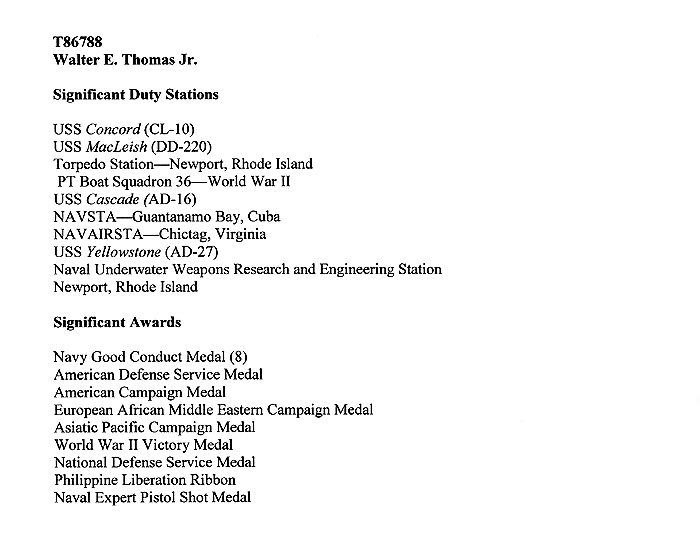

86784  86788

86788  86796

86796

86934

86934  87030

87030

87036

87036  87077

87077

87132

87132  87221

87221

87294

87294  87298

87298  87339

87339

William Dwight Chandler , Jr.

Date of death: 25-May-77William Chandler graduated from the U.S. Naval Academy at Annapolis, Class of 1911. He retired as a U.S. Navy Captain.

AWARDS AND CITATIONS

Navy Cross

Awarded for actions during the World War I

The President of the United States of America takes pleasure in presenting the Navy Cross to Lieutenant Commander William Dwight Chandler, Jr., United States Navy, for distinguished service in the line of his profession as Commanding Officer of the U.S.S. MacDONOUGH, engaged in the important, exacting and hazardous duty of patrolling the waters infested with enemy submarines and mines, in escorting and protecting vitally important convoys of troops and supplies through these waters, and in offensive and defensive action, vigorously and unremittingly prosecuted against all forms of enemy naval activity, during World War I.

Action Date: World War I

Service: Navy

Rank: Lieutenant Commander

Company: Commanding Officer

Division: U.S.S. MacDonough

Submitted by Doug Bewall RMCM USN Ret

87354

Navy Log Entry

November 25, 1975, single engine E-1B, Bureau Number 148909, on climb out off the USS Oriskany, CVA-34: The sea state at the carrier was too great, 16 plus foot swells, to allow a single engine arrested landing aboard the ship. The aircraft was bingoed to Cubi Point, Philippines, 110 miles away. Fuel was dumped, and NFO, LT Zip Ziemer, threw out electronic gear to lighten the aircraft. Aircraft continued to lose altitude until it flew into ground effect at about 80 feet above the ocean. Once the aircraft flew into Subic Bay, it again lost altitude to about 30 feet above the bay. It was so low that it had to fly around Grande Island for a straight in landing at Cubi Point. Upon landing the one good engine quit. Maintenance found no measurable fuel in the aircraft’s tanks and had to do a double engine change. Plane Commander LT Bill Leins and Copilot LTJG Larry Rhea did an excellent job of saving the crew, for it is felt that if we had ditched the aircraft in the high sea state, the crew would not have survived

87400 87489

87489

87506

87506  87557

87557 My Dad suffered thru the depression and in the fall of 1940 he volunteered for the Civil Conservation corps program which was part of the United States Army. My Dad went to Alexandria, Virginia to work on the old Army base called Fort Hunt. Today Fort Hunt is a national park, which during the Second World War was a place that held German prisoners of war. All my Dad ever told me about his time at Fort Hunt was dodging Hillbillies who were upset at them for fooling with their daughters.

On December seventh of 1941 the United States was attacked by the Japanese at Pearl Harbor and Wake Island. The next day my Dad enlisted in the military. He wanted to be a Marine but instead chose to be a sailor. His became a Machinist Mate using many of the skills that he learned working with my Grandfather in the hills of Manayunk.

I remember being 17 and thinking I knew everything but could not imagine what he did at that age. My Dad after boot camp in Great Lakes, Chicago was assigned to the brand new USS Indiana battleship at Newport News, Virginia. He would be one of the original plank holders who put her into service. After shakedowns and training they left Hampton Roads, Virginia and traveled thru the Panama Canal. The "Virgin ark" arrived at New Caledonia in the south Pacific in November of 1942 and soon engaged the enemy. Their first task was to protect the carriers Saratoga and Enterprise as well as secure the slot against the Tokyo express. The Marines were on Guadalcanal and the future looked bleak. After Guadalcanal was held, my Dad took part in raids in the Marshall, Gilbert and Solomon Islands. Her main task still was to protect the fast carriers.

Soon after the landings on Tarawa the USS Washington collided with the USS Indiana at nighttime. A large number of lives were lost in this collision. My Father was on watch down in the engine room and got shaken up. The Indiana was taken to Bremerton, Washington for repairs but soon returned to the South Pacific.

The next task was to knock out the large Japanese Naval base at Truk Atoll. This would be revenge for Pearl Harbor when the Japanese attacked our main naval base.

My Dad next took part in the Battle of the Philippine sea which was also to be known as the Great Mariana turkey shoot due to the annilation of the Japanese air power by our brave pilots and guns of the fleet. This all took place during the taking of the islands Tinian, Guam and Saipan. I recall my Father telling about seeing the Japanese civilians jumping to their deaths from the cliffs on Saipan.

My Dad then took part in the bombardment of the island of Palau so the Philippines could be liberated. Palau was a Japanese fighter base, which McArthur felt needed to be taken. After this invasion was completed the Indiana headed to Pearl for repairs while my Dad got much needed rest. The battle of Leyte Gulf took place while my Dad was lying on the beach and doing the hula.

After the Indiana was repaired my Dads vacation was over and they then took part in the bombardment of Ivo Jima and Okinawa. At this time the Japanese sent the massive battleship Yamato to sea. The task force that the Indiana was part of hunted down the Yamato and put her under the waves. Soon after the landings on Okinawa the fleet encountered a terrible Typhoon which sank a large number of ships.

During this period the Japanese were employing suicide planes against the American fleet. One struck the Indiana earlier off the coast of Saipan. Luckily the Kate bomber did not explode and no lives were lost. Again I am reminded of being at my Fathers age and thinking I knew it all. I wasn't even close.

In 1945 victory would come over Japan. Five months shy of his twenty first birthday, my Father had lived more then most of us will in an entire lifetime. My Dad would continue to serve his country proudly for seventeen more years before retiring and becoming a mailman. He would serve on other ships in the coming years but none would endear him like the USS Indiana. They went into harms way and survived. My Father served on the cruiser USS Toledo, as well as the Ajax and Pollock. He was stationed in the Philippines for five years as well as Japan, San Diego and finally Treasure Island where he met my Mother.

My Father was a member of the greatest generation and my hero

87646  87737

87737  87825

87825  87908

87908

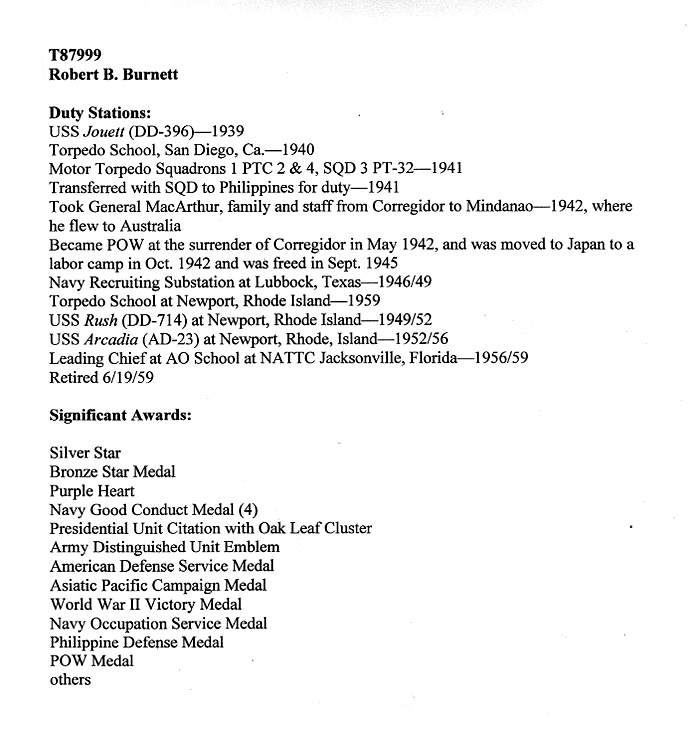

87999

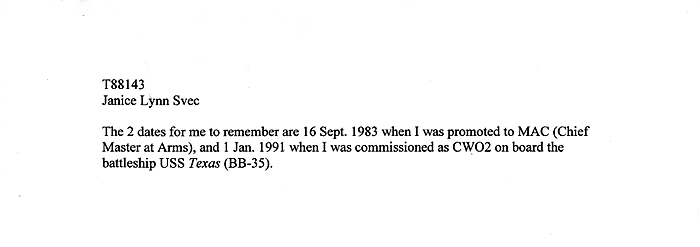

87999  88143

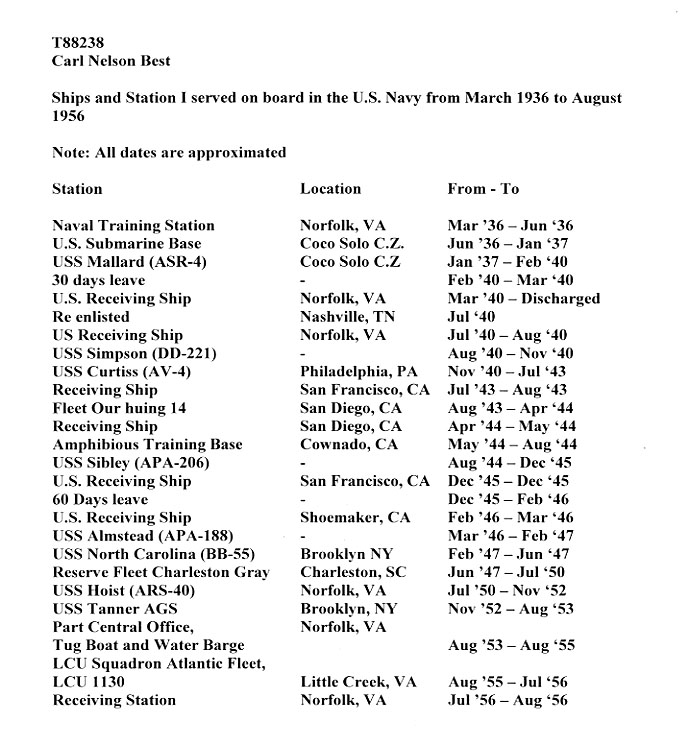

88143  88238

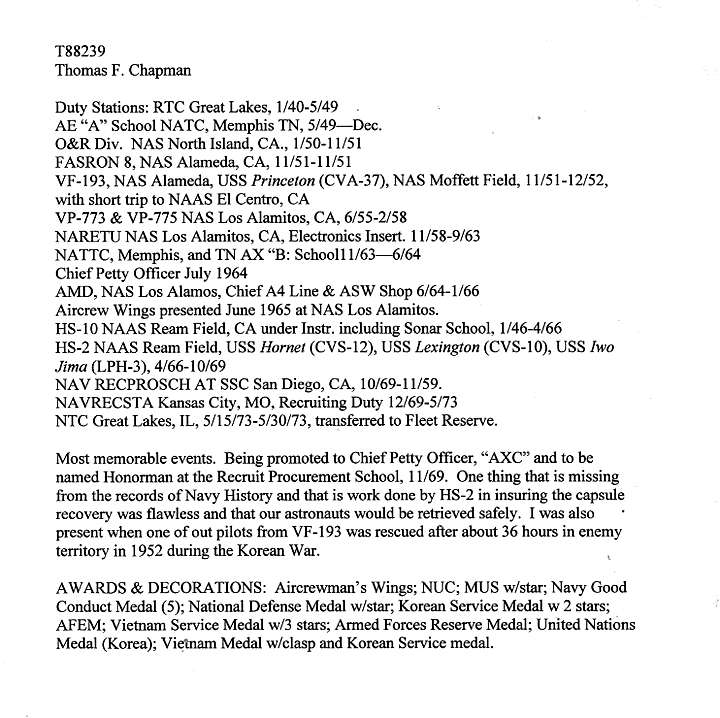

88238  88239

88239  88243

88243  88367

88367  88465

88465  88520

88520  88733

88733  88756

88756  88792

88792  88999

88999  89023

89023

|

Name: |

USS Bismarck Sea |

|

Builder: |

|

|

Laid down: |

31 January 1944 |

|

Launched: |

17 April 1944 |

|

Commissioned: |

20 May 1944 |

|

Fate: |

Sunk by kamikazes[1] during the Battle of Iwo Jima on 21 February 1945 |

During July and August 1944, Bismarck Sea escorted convoys between San Diego, California, and the Marshall Islands. After repairs and additional training at San Diego, she steamed to Ulithi, Caroline Islands, to join Admiral Thomas C. Kinkaid's 7th Fleet. During 14-23 November 1944, she operated off Leyte in support of the operations and later took part in the Lingayen Gulf landings (9-18 January 1945). On 16 February, she arrived off Iwo Jima to support the invasion.

On 21 February 1945, despite heavy gunfire, two Japanese kamikazes hit the

According to the Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships, Edmonds directed the rescue operations of the remaining hands, saving 378 of the carrier's crew including the commanding officer, in spite of darkness, heavy seas and continuing air attacks. Thirty of

89171

89245

89245

89263

89263  89343

89343 DEPARTMENT OF THE NAVY -- NAVAL HISTORICAL CENTER

805 KIDDER BREESE SE -- WASHINGTON NAVY YARD

WASHINGTON DC 20374-5060

805 KIDDER BREESE SE -- WASHINGTON NAVY YARD

WASHINGTON DC 20374-5060

Oral History-Battle for Okinawa, 24 March -30 June 1945

Recollections of Commander Frederick Julian Becton, USN, Commanding Officer of the destroyer USS Laffey (DD-724) which, despite being struck by eight Japanese suicide (kamikaze) aircraft on 16 April 1945, did not sink.

Adapted from Frederick Julian Becton interview in box 2 of World War II Interviews, Operational Archives Branch, Naval Historical Center. I am Commander Frederick Julian Becton, Commanding Officer of the USS Laffey. The Laffey was built in Bath, Maine and was commissioned in Boston, Massachusetts, at the Navy Yard on February 8th, 1944.

After a brief shakedown period, the ship participated in the Normandy Invasion in June 1944, after which she took part in the Cherbourg [France] bombardment on June 25th, 1944 and suffered an eight-inch [German artillery shell] hit which fortunately did not explode.

Upon returning to the States for repairs and alterations, the ship proceeded to the Pacific and joined Admiral [William F. Bull] Halsey's Third Fleet in November, 1944, for strikes against the Philippine Islands during the month of November.

The ship joined the 7th Fleet under Admiral Kinkaid at Leyte Gulf [Philippines] in early December, 1944 and took part in the landing of the 77th Division of the U.S. Army at Ormoc Bay, on December 7th, 1944. This was our first experience with the Kamikaze Suicide Corps [units of Japanese aircraft turned into flying bombs intended to be crashed by their pilots into U.S. Navy ships to sink or severely damage them]. The ship and the whole convoy were under incessant attacks from about 10 o'clock in the morning until dark that evening.

The next landing the ship participated in was at Mindoro on December 15,1944.

The next landing was about two weeks later when the ship left Leyte Gulf on January 2nd, and proceeded to Lingayen Gulf [also in the Philippines] to assist with the softening up activities and bombardment prior to the Army landing on January 9th, 1945.

We remained in the Lingayen Gulf area until about the 22nd of January and then proceeded to join Admiral Mitcher's task force at Ulithi.

Participated in Tokyo Strikes.

The next operation in which the ship participated was the strikes on Tokyo in mid-February 1945, after which the carrier task groups headed south to support the Iwo Jima landing. We went back for the second strikes on Tokyo about the 24th of February, and returning from that, went into Ulithi where we remained until we were ready for the Okinawa operation.

We departed Ulithi for the Okinawa landings on the 21st of March, arrived at Okinawa the 24th of March, and performed screening duties with the battleships and cruisers [protecting them from Japanese aircraft and submarines] who were bombarding the beaches until the major landing on April 1st, 1945. Thereafter, we took up station to the north of Okinawa at radar picket station number one about 35 miles north of Okinawa [these picket stations gave advance warning of the approach of enemy aircraft or ships].

Our tour of duty on this picket station was uneventful until the morning of April 16th, when we underwent a concentrated attack by Japanese suicide planes. The attack commenced about 8:27 [a.m.] when we were attacked by four Vals [single-engine Japanese Aichi D3A naval dive bomber with a 2-man crew], which split, two heading for our bow and two swinging around to attack us from the stern. We shot down three of these and combined with a nearby LCS [support landing craft] in splashing the fourth one. Then two other planes came in from either bow, both of which were shot down by us. It was about the seventh plane that we were firing on that finally crashed into us amidships and started a huge fire. This marked us as a cripple with the flames and smoke billowing up from the ship and the Japs really went to work on us after that.

Two planes came in quick succession from astern and crashed into our after [rear of the ship] five-inch twin mount. The first one carried a bomb which exploded on deck. The second one dropped its bomb on deck before crashing into the after mount. Shortly thereafter, two more planes came in on the port quarter crashing into the deckhouse just forward of the crippled after five-inch mount. This sent a flood of gasoline into the two compartments below the after crew's head [bathroom] and with the fire that was already raging in the after crew's compartment just aft of the five-inch mount number three, we now had fires going in all of the after three living spaces, besides the big fire topside in the vicinity of the number four 40 mm [antiaircraft gun] mount.

The two planes... no, the next one was a plane from our port quarter that dropped a bomb just about our port [left] propeller and jammed our rudder [steering mechanism] when it was 26 degrees left.

Strafed by Approaching Plane.

The next plane came from the port bow, knocked off our yardarm [a horizontally-mounted spar on the radar/radio mast], and a [F4U] Corsair [single engine US fighter with a 1-man crew] chasing it, knocked off our Sugar Charlie [SC air search] radar. Then a plane came in from the port bow carrying a big bomb and was shot down close aboard [in the water near the ship's side]. A large bomb fragment from the exploding bomb knocked out the power in our number two five- inch mount which is the one just forward of the bridge. Shortly thereafter this mount, in manual control, knocked down an Oscar [single-engine Japanese Nakajima Ki-43, Army-type fighter with a 1-man crew] coming in on our starboard bow [from the right-front of the ship] when it was about 500 yards from the ship. At the same time the alert mount captain of number one five- inch mount sighted a Val diving on the ship from the starboard bow, took it under fire and knocked it down about 500 yards from the ship using Victor Tare projectiles. The next plane came yardarm as it pulled out of its dive. It was shot down by the Corsairs ahead of the ship.

The next plane came in from the starboard bow strafing [firing its machine guns] as it approached and dropped a bomb just below the bridge which wiped out our two 20 mms [antiaircraft guns] in that area and killed some of the people in the wardroom [officers' dining and social compartment] battle dressing station. This plane did not try to crash either, and was shot down, after passing over the ship, by our fighter cover.

The last plane that attacked the ship came in from the port bow, and was shot down by the combined fire of the Corsair pilots and our own machine guns, and struck the water close aboard and skidded into the side of the ship, denting the ship's side but causing no damage.

The action had lasted an hour and 20 minutes. We had been attacked by 22 planes, nine of which we had shot down unassisted, eight planes had struck the ship, seven of them with suicidal intent, two of these seven did practically no damage other than knocking off yardarms. Five of these seven did really heavy material damage and killed a lot of our personnel. We had only four of our original eleven .20 mm mounts still in commission. Eight of the original 12 barrels of our .40 mm mounts could still shoot but only in local control, all electrical power to them being gone and our after five-inch mount was completely destroyed. Our engines were still intact.

The fires were still out of control and we were slowly flooding aft. Our rudder was still jammed and remained jammed until we reached port. We tried every engine combination possible to try to make a little headway to the southward but all no avail. We had lost 33 men, killed or missing, about 60 others had been wounded and approximately 30 of these were seriously wounded.

The morning of our attack off Okinawa we had a CAP [combat air patrol] of about 10 planes over us. It was entirely inadequate for the number of attacking Jap planes. Our own radar operators said that they saw as many as 50 bogies [Japanese aircraft] approaching the ship from the north just prior to the attack. Many more planes were undoubtedly sent to our assistance and quite a large number of Jap planes were undoubtedly shot down outside of our own gun range and to the north of us that morning. When the attack was all over we had a CAP of 24 planes protecting us.

Threw live bomb over the side.

One of the highlights of the action occurred when Lieutenant T.W. Runk, [spelled] R-U-N-K, USNR, who was the Communications Officer on the Laffey at the time, went aft to try to free the rudder. He had to clear his way through debris and plane wreckage to reach the fantail [rearmost deck on the ship] and, on his way back to the steering engine room, saw an unexploded bomb on deck which he promptly tossed over the side. His example of courage and daring was one of the most inspiring ones on the Laffey that morning.

Another example of resourcefulness exhibited that morning came when two of the engineers, who were fighting fires in one of the after compartments, were finally driven by the heat of the planes [flames] into the after Diesel generator room. The heat from the burning gasoline scorched the paint on the inside of the Diesel generator room where there was no ventilation whatsoever. The acrid fumes almost suffocated these two men but they called the officer in charge of the after engine room, which was in adjacent compartment, and told him of their predicament. He immediately had one of the men beat a hole through the bulkhead with a hammer and chisel and then, with and electric drill, cut a larger hole to put an air hose through to give them sufficient air until they could be rescued. At the same time other engineering personnel had cleared away the plane wreckage on the topside and with an oxime acetylene torch cut a hole through the deck which enabled these two men to escape. Upon reaching the topside, both of them turned to fighting the fires in the after part of the ship.

The morning after the action we removed one engine from the inside of the after five-inch mount which had been completely destroyed and which had had its port side completely blown off by the explosion of the initial plane, which was carrying a bomb when it crashed into this mount. The second plane which crashed into that mount had also done great damage to it. And the next morning we pulled one engine out of the inside of the mount and another engine was sitting beside the mount with the remains of the little Jap pilot just aft of the engine. There was very little left of him, however.

We transferred our injured personnel to a smaller ship that afternoon, which took them immediately to Okinawa. We were taken in tow by a light mine-sweeper in the early afternoon, about three hours after the attack and the mine-sweeper turned the tow over a short time later to a tug, which had been sent to our rescue. Another tug came alongside us to assist in pumping out our flooded spaces and with one tug towing us and the other alongside pumping us, we reached Okinawa early the next morning.

Put soft patches on hull.

After reaching Okinawa and pumping out all our flooded spaces, we put soft patches on four small holes we found in the underwater body in the after part of the ship. It took about five days to patch the ship up sufficiently for it to start the journey back to Pearl Harbor.

After leaving Okinawa we proceeded to Saipan and thence to Eniwetok and from Eniwetok on to Pearl Harbor.

About the seventh plane that attacked us, it came in on the port bow and he was low on the water and I kept on turning with about 25 degrees left rudder towards him to try to keep him on the beam. He swung back towards our stern and then cut in directly towards our stern and then cut in directly towards the ship. I kept turning to port to try to keep him on the beam and concentrate the maximum gunfire on him and as we turned, we could see him skidding farther aft all the time. I finally saw that he wouldn't quite make [it to hit] the bridge but then I was afraid he was going to strike the hull in the vicinity of the engine room, but about a hundred yards out from the ship, he finally straightened out and went over the fantail nicking the edge of five-inch mount three and then crashed into the water beyond the ship.

Of course, many people have various ideas about how to avoid these Kamikazes but the consensus of opinion, so far as I know, to try to keep them on the beam [i.e., coming in on a 90- degree angle to the long axis of the ship, or directly from the side] as much as possible or one reason to concentrate the maximum gunfire on them as they approached. And another reason is to give them less danger space by exposing just the beam of the ship rather than the quarter of the bow for them to attack from. The danger space is much less if they come in from the beam than it would be if they came in from ahead or from astern and had the whole length of the ship to choose in which to crash into. High speed and the twin rudders, with which 2200 ton destroyers are equipped, were believed to have been vital factors in saving our ship that morning off Okinawa.

Interviewer:

Captain Becton, were you on some other destroyer in the early part of the war?

Commander Becton:

Yes, I was in the [USS] Aaron Ward [DD-483] in the early part of the war. I was in the [USS] Gleaves [DD-423] when the war was first declared, but went to the Aaron Ward a short time after that as Chief Engineer, fleeted up [was promoted] to Exec[utive Officer - second in command] and was in there when she went through that night action off Guadalcanal the night of 12-13 November 1942. We were hit by nine shells that night, varying between 5 and 14 inches, but fortunately they were all well above the water line. We were towed into Tulagi [an island near Guadalcanal] the next day and later repaired.

Interviewer:

Were you also on board when the Ward went down?

Commander Becton:

Yes, I was on board the Aaron Ward when she sank off Guadalcanal in April, 1943. After that I went to the squadron staff of ComDesRon [Commander, Destroyer Squadron] 21 and went through three surface actions in the [USS] Nicholas [DD-449]. The first of these was the night of 6 July, in the First Battle of Kolombangara or Kula Gulf when the [light cruiser USS] Helena [CL-50] was sunk. The Nicholas and the [destroyer USS] Radford [DD-446] stayed behind after the cruisers and other destroyers retired to pick up the Helena's survivors and fight a surface action with Jap ships that were still there in Kula Gulf.

The next surface action we were in came a week later when the same outfit of destroyers and cruisers attacked some more Jap cruisers and destroyers that were coming down from the northwest. We operated under Admiral Ainesworth that night. The destroyers were under the overall command of Captain McInerney.

After that the next surface action we were in was after the occupation of Vella Lavella, in which we took on some Jap destroyers and barges [towed craft carrying troops or cargo] to the north of Vella Lavella in a night action. The destroyers turned and ran and left their barges and we couldn't catch the destroyers. We did some damage to them, possibly destroyed some, but the major damage was done to the barges which they had left behind and many of which we sank.

Note: USS Laffey survived WWII and is now a memorial ship which can be visited at Patriots Point Naval & Maritime Museum in Mount Pleasant, South Carolina.

19 February 2001

89451

89633

89633  89689

89689  89742

89742

89822

89822

89870

89870  89878

89878  89890

89890

89983

89983

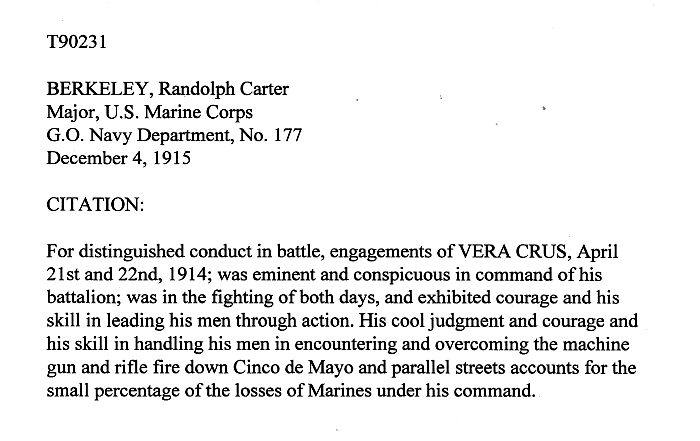

90231

90231  90235

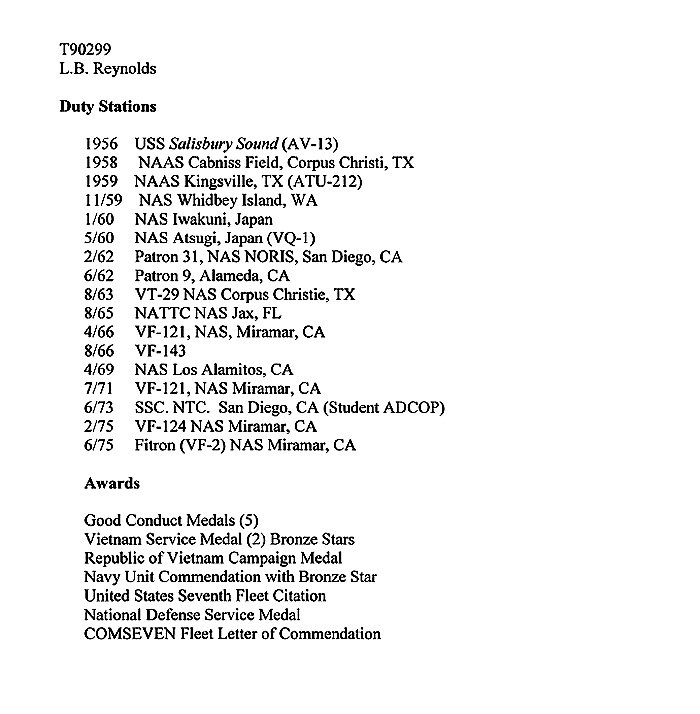

90235  90299

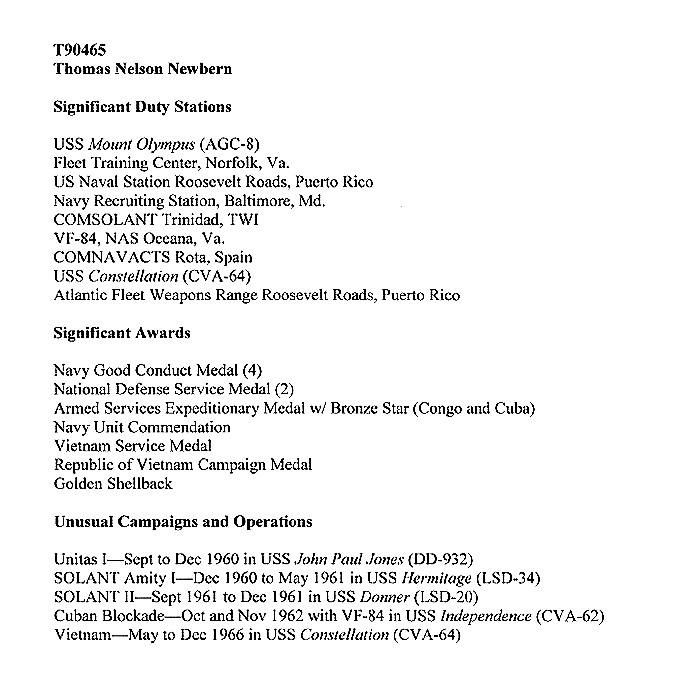

90299  90465

90465  90630

90630  90804

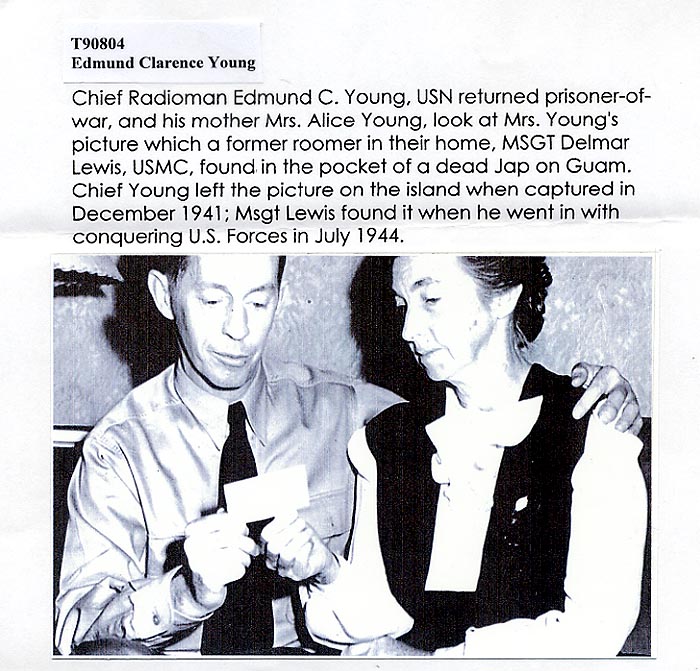

90804  90853

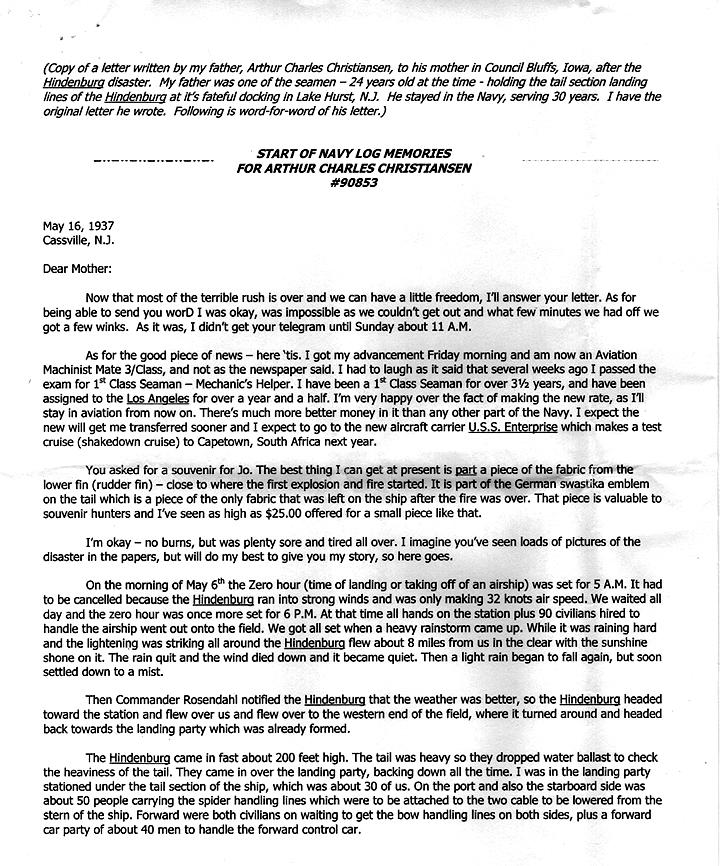

90853

90880

90880

90946

90946  91010

91010  91025

91025  91045

91045  91053

91053  91077

91077  91094

91094

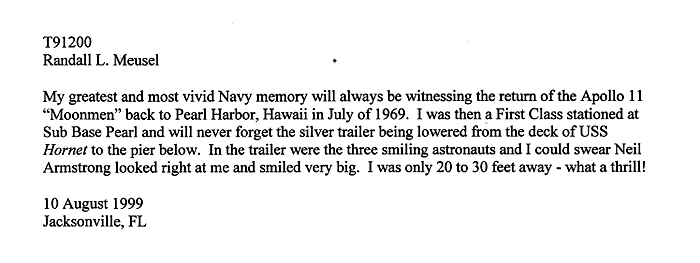

91200

91200  91211

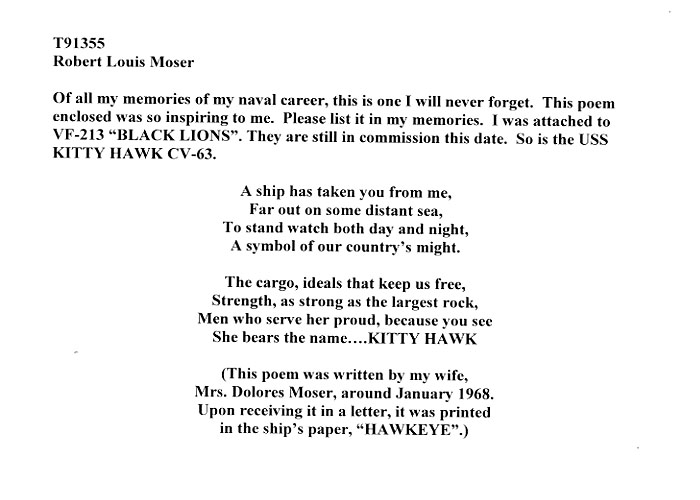

91211  91355

91355  91449

91449  91506

91506

91525

91525  91545

91545

91640

91640  91696

91696  91832

91832 Franklin Parant Reggero has gone home to be with the Lord Jesus and be reunited with his two sons: Franklin O. and Ronald M., who predeceased him. He leaves behind to cherish his memory, his childhood sweetheart whom he married on July 18, 1941, Virginia (Drake) Reggero and his two daughters: Virginia (Ginny) Taegder McCue (Joe) and Michele (Shelly) Starkey (Keith Cardish); six grandchildren and twelve great-grandchildren.

He was the son of Nicholas Ruggiero and Edith Parant Ruggiero and was predeceased by all five of his siblings: Mary Swaida, Edith Bell, John Reggero, William Reggero and Alice Gowdey.

Franklin was born and raised in his beloved City of Newburgh (on Colden Street) back in the day where his father was one of the few on the block who owned a radio and often placed it in the window for the neighbors to hear. As a young boy, Franklin was very active in all kinds of sports and received numerous awards and trophies for his involvement in the YMCA in swimming, tennis and pole vaulting. He was also involved in the Newburgh fast-pitch softball league, the Newburgh Bowling Association and the New York State Amateur Boxing Program. He trained with some of the all-time great boxers like Tony Zale and Sugar Ray Robinson during the 1940s. When he boxed in the Golden Gloves in Madison Square Garden in New York City, Tony Zale's manager took him under his wing and coached Frank during his match and he won the fight.

When the bombs landed on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941 and the President declared War, Franklin enlisted in the Navy to defend his homeland. Because of his experience in the medical field, he was assigned to a sub chaser (PC 1213) and became the ship's medic. His shipmates called him Doc at all of his Navy reunions following the end of the War and for many years after. Frank's Patriotism never wavered and he was proud to have served his country, but it was his love for his family that remains his legacy. Generations to come will hear his many stories that he left behind.

Following his service to his country in World War II, he returned to Newburgh and his wife and firstborn and went to work at the Newburgh Felt Mill for several years. He accepted a position with the newly formed IBM Corporation and after 30 years of dedicated and distinguished service, he received the coveted IBM President's Award. His career at IBM included his service to NASA during the 1960s when JFK initiated the Space Program and Frank would be privileged to be a part of the Project Mercury team at the Goddard Space Flight Center in Maryland. He was the Special Operations Manager at Goddard.

Frank joined the Black Rock Fish & Game Club with his brothers: John and William in 1946 and they were a few of the founding members at Black Rock. Throughout the years, Frank held every office in the Club including President, Treasurer, Member Secretary, Director and Chairman of Work Committees to name just a few. He remains the only Black Rock Member to be elected to every officer chair including the President's seat. The meeting hall at Black Rock Fish & Game Club was dedicated to him for his past service. Frank utilized that meeting hall every single Friday night to meet with his beloved card players.

Frank passed at home on Hospice, surrounded by his family whom loved him dearly and are now devastated by his passage. We did not "lose" him, we have lost sight of him only until the Lord calls us home to Heaven to be reunited with him.

_______________________________________________________________

It sounds like a fairytale or a Hallmark movie but it is the true love story of two people that has spanned their entire lives – all 92 years of them and it all began in Newburgh.

In 1921 in Newburgh, Colden Street was the hub of the City. You could get anything your heart desired from any of the variety of ethnic delicatessens on the block.

Franklin Parant Reggero, the infant son of Nicholas and Edith Reggero, was sleeping in his Aunt Anna Parant’s apartment bedroom on Colden Street in Newburgh 1921. Minnie Drake was walking down Colden Street carrying her infant daughter, Virginia, just 3 months old when she decided to stop and visit her friend. Anna suggested placing baby Virginia next to the other sleeping baby, Franklin, on the bed while the two women shared a cup of tea.

Fifteen years would pass before Franklin and Virginia would meet up again and it would be their affection and tenderness towards the orphans that they visited on Grand Street in Newburgh that would bring the two together again. Virginia was bringing some candy to the little girls in the orphanage on Grand Street when a young boy outside the orphanage told her about a young man who often brought candy to them. Virginia remarked that he must be a kind-hearted soul. The little boy was insistent that Virginia come and see the boy who was an athlete who often pole vaulted at the YMCA. He told Virginia that Franklin was there right now and she should come to the fence to see him.

Virginia followed the youngster and peeked over the fence just as Frank spotted her and pole vaulted right in front of her. It would be love at first sight. Since Virginia was only 15 years of age, her father would not let her date the young Italian from the other side of town who followed her all the way home to her apartment on 437 Broadway. Franklin would have to wait until Virginia turned 16 years old before her father would allow her to date. Even then, only if her mother, Minnie, chaperoned them on all of their dates to the Ritz Theater on Broadway in Newburgh. The couple fondly remembers that in those days for the price of admission (about 10 cents) you also received a piece of depression glassware.

The couple would continue to date throughout their high school years at the Newburgh Free Academy.

They married on July 18, 1942 after Frank returned home on a Navy pass during WWII but not without a struggle. The City Hall was closed that weekend but luckily for the couple they were able to locate the caretaker who felt sorry for the sailor and his fiance and called the Newburgh City Clerk at home. The couple was issued a marriage license. They were married at the parsonage at the Good Shepherd Church on Lander Street and a small reception followed at the Hasbrouck Tavern in the Town of Newburgh. Because it was during the Depression, there were no wedding gifts given with the exception of one lone teakettle that someone brought them. The juke box had only one fast song on it: “Bells that Jingle Jangle Jingle – aren’t you glad you’re single.” Everyone played it over and over again and danced the night away.

It’s been 72 years, four children, six grandchildren and twelve great-grandchildren and the Reggero’s were still enjoying their wonderful life together. It wasn’t always an easy life and they had to bury both of their sons but still, they kept on leaning on each other, trusting God and loving their family. They made it through the tough times and they kept the rest of us going.

It was the Reggero’s selfless giving unto others that brought them together in the first place and their constant caring for one another has kept them together all of their years. For the couple’s fiftieth wedding anniversary, their children chose a song by Vince Gill called, “Look at Us.” The lyrics say in part, “In a hundred years from now I know without a doubt, they'll all look back and wonder how we made it all work out, chances are we'll go down in history, when they want to see how true love should be, then just look at us.”

It won’t take one hundred years for us to wonder how this couple managed to come so far together and it all began on Colden Street in Newburgh in 1921 during a magical time in the lives of so many who remember the grandeur of Newburgh.

We love and miss you Pop, and we promise to take care of Mom for you. Rest in the arms of Jesus until we meet again in God's Glory.

91909

91909

92035

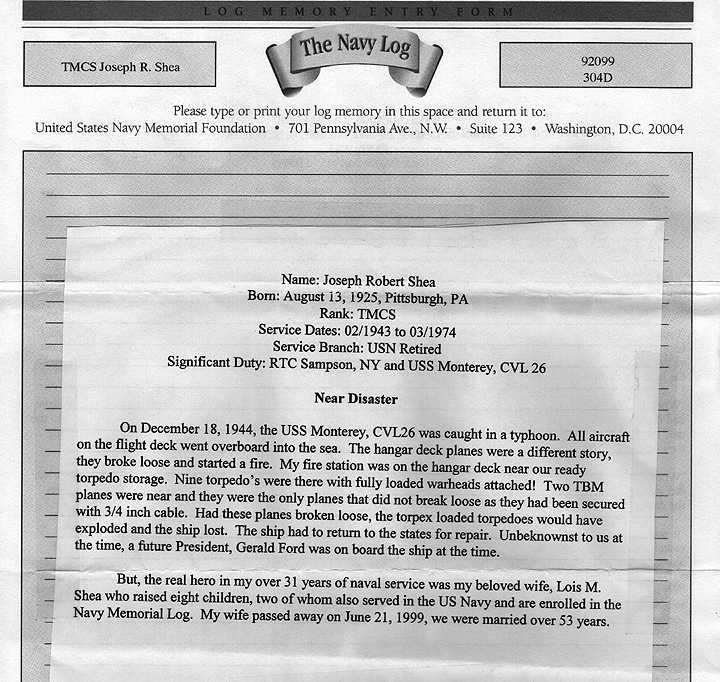

92035  92099

92099  92100

92100

T92100

C. W. Hunter

MEMORIES

1951-1971

These memories were assembled for the purpose of the Navy Memorial in Washington, DC, and are in no particular order, rather as they are recalled or come to mind.

- Completed around the World voyage on USS Forrest Royal DD-872. Began and

ended at the port of Newport, RI. Sailing west on 8/2/54 and finished 3/14/55.

(Ancient order of Magellan membership). Sailed >39,000 miles during this period. - Crossed the Arctic Circle on USS Forrest Royal 16 Sept. 1952 off north coast of

Norway. - 1958 Commissioned USS Hull DD-945 at Boston, MA, (Plank owner). Home port

to be San Diego, via Panama Canal. - Made five submarine dives on USS Redfish SS-395 off Guam 1959.

- 1960 Commissioned USS Coontz DLG-9, Bremerton, WA, (Plank Owner).

Carrie, our first child was born. - 1968 Landed on aircraft carrier USS Yorktown in the sea of Japan, flight deck

covered with ice. (Yorktown now a Memorial in Charleston, SC) Next morning,

flew off in helicopter and was lowered onto a rocking, rolling, cold destroyer DD-

885 for duty. - Seventeen years sea duty out of twenty, all on Destroyers. (51 - 71)

Three years as Company Commander RTC San Diego. (64 - 66) - Crossed Equator seven times, first time on 01/27/55. Longitude 103-55' East,

Latitude 00-00. (5-times on DD-872,1-time on DLG-9,1-time on DD-945.) - Five Vietnam tours, shore bombardment / carrier plane guard duty, Yankee

Station, Tonkin yacht club.

10. Two or three Mediterranean voyages plus one to northern Europe, 1952, 1957,

11. 1957 Circled Africa on DD-872. We were in Athens Greece when the Suez Canal was bombed and had to sail around Africa to the Red Sea. Returned home the same route. (Christmas in Cape Town, South Africa.)

12. 1962 Circled Australia aboard the USS Coontz. We were in Perth Australia the

night John Glenn first orbited the earth. The city of Perth turned on its lights all

over town. Glenn commented as he flew over Western Australia that he could see a

bright spot down there and that was confirmed to be Perth. Other ports of call Albany, Sidney & Melbourne.

13. 1961 While visiting the port of Chinhae, South Korea, the then President Park

Chunghee, came aboard to visit the new pride of the fleet, (guided missile destroyer

leader USS Coontz). During his visit I was introduced to him, and we shook hands.

This ship, in thirty minutes, could deliver more destructive power than the entire

fleet during World War II.

Karen, our second child was born.

- 1953 While sailing between the toe of Italy and Sicily at night (Straits of

Massina), Mt. Stromboli was very close and glowed from the lava within. - 1953 Sailing up the Elbe River to Hamburg, Germany, after dark during a

heavy snow storm made for a very beautiful sight with Christmas lights on both

sides of a busy river. On to London, England, for a very British Christmas and New

Year. - 1959 Going topside at sunrise on the first morning after arrival in the waters off

Japan, there stood a giant mountain named Mt. Fujiyama (Fuji-san). A most

impressive first site of the land of the rising sun. A massive mountain with a very

large snow cap and just off the seashore as if rising out of the Ocean. - Sailing out of Sidney, Australia, en route to San Diego, CA. The voyage took

over six weeks and we made two overnight fuel stops, the first being Pago Pago,

Samoa. This was 1962, a long time before satellites or any modern communications

now considered common. Pago Pago was as far from civilization as one could get at

that time. Natives came out in hand-paddled boats to meet us. Men and women in

grass skirts dancing on an old wooden pier. Just as in the movies. - 1957 Sailing out of Cape Town, South Africa, en route to the Red Sea we

continued on to the north end of the Persian Gulf into the Tigris/Euphrates River to

Basra, Iraq. Basra is the back door to Mesopotamia, the Garden of Eden and the

Cradle of Civilization. - 1956 While in the Caribbean for six weeks of underway training visited the old

capital city of Santiago de Cuba. Fidel Castro was not yet known. Later sailed on

to Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, on a Midshipmen voyage. First trip to Rio earlier in 50's. - 1950's On two or three return trips to the states from the Mediterranean, we

made overnight fuel stops at a place called Ponta Delgada in the Azores Islands.

The natives were all Portuguese and very friendly. What I remember most is that

the men were all well dressed but never wore anything on their feet. On Sundays they were dressed in coats, ties, hats and no shoes. Almost all transportation was horse drawn. The Azores were off of most shipping lanes in those days, much like Samoa, modernization came slow if at all prior to satellites.

- 1955 While in transit of the Suez Canal, at times, one could see the Pyramids in

the far off distance and up close camel caravans coming down to the Red Sea for

salt. Very picturesque and memorable. A large, large light is hung from the ships

bow for night steaming in a very narrow shallow canal, as it takes almost 24 hours

to complete the transit. - 1954 During the around the world voyage on the Royal, one of our many ports

of call was Hiroshima, Japan, the site of the first atomic bomb drop nine years

earlier. Little if any of the city had been rebuilt, total and complete destruction as

far as one could see. Of those who survived, many had very serious radiation burns.

Some, still in shock, would just wander and wander the bombed out area that had

once been their neighborhood. I remember making one visit to ground zero — once

was enough! - Numerous Hong Kong, China, visits between 1954-1970. Each visit provided

memories that one ought not forget, but I'm afraid that process may have begun. In

brief, many changes were taking place in Hong Kong during this period. China, as

you know, is a world unto its own. This was during the time of Mao and

communism. It now seems the more things changed, the more they stay the same.

Yes, grandchildren, these travels were all by water, and yes, all were a long way from Shelbyville Illinois, both literally and figuratively speaking.

These memories are but a few of my twenty years in the Navy. Now, many years later, that period remains of life-long importance to me. Naval service provided many intangible benefits to a young recruit who later chose it as a career. Memories of old seem to confirm that one tends to remember the good times and not the bad, as we sailed war zone waters during both the Korean and Vietnam wars for long periods on numerous voyages. A Senior Chief in Engineering, my many power propulsion crews worked hard for every nautical mile sailed, yet traveled the world far more than did the "old salts" of yesteryear. Each entry in this memorandum is well documented in the respective ships log and voyage books on file.

Water water everywhere but not a drop to drink

Modern day technology (computers and satellites) provide little help when trying to describe the vastness of the Seven Seas. Old Sea Stories and/or Sea Lore of the Ancient Mariners are all very descriptive, while being perhaps, a bit short on accuracy. The indescribable size of the Oceans or how the giant storms can turn the sea into a living hell simply can't be passed on in any realistic way and remain unbelievable.

A huge debt of gratitude with love, respect, and admiration I owe to my family members that were left behind during these many long periods, Wife, Daughters, Mother, Father, and Sisters. A Navy wife that's left alone to do it all, also far from home, never receives the credit that's due them. The time that they serve is equal to, if not more difficult than, that of the serviceman. On all accounts, I was indeed fortunate and blessed.

ANCHORED IN THE HAVEN OF REEF

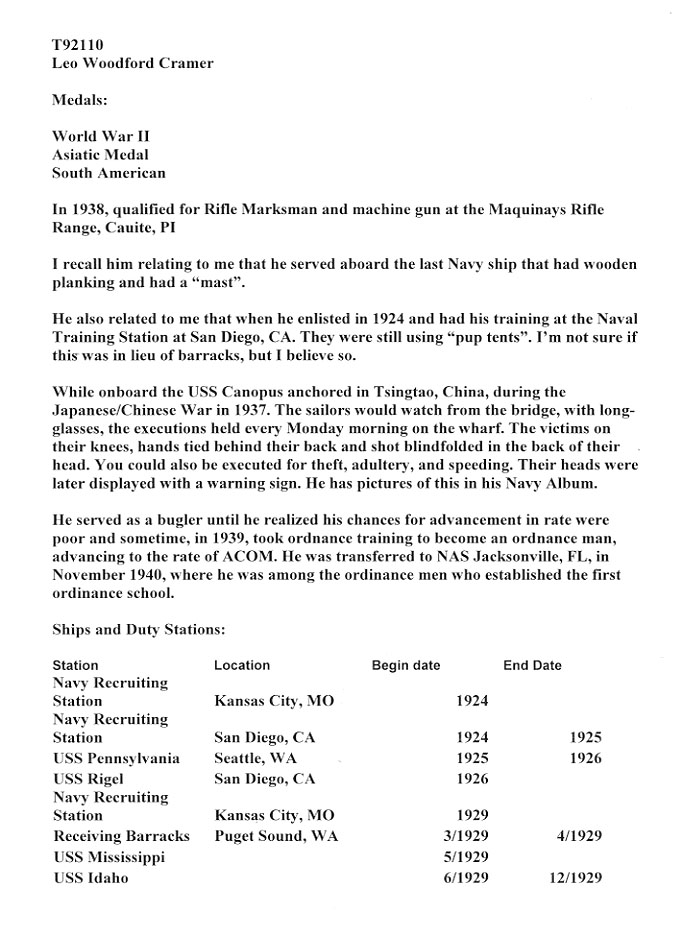

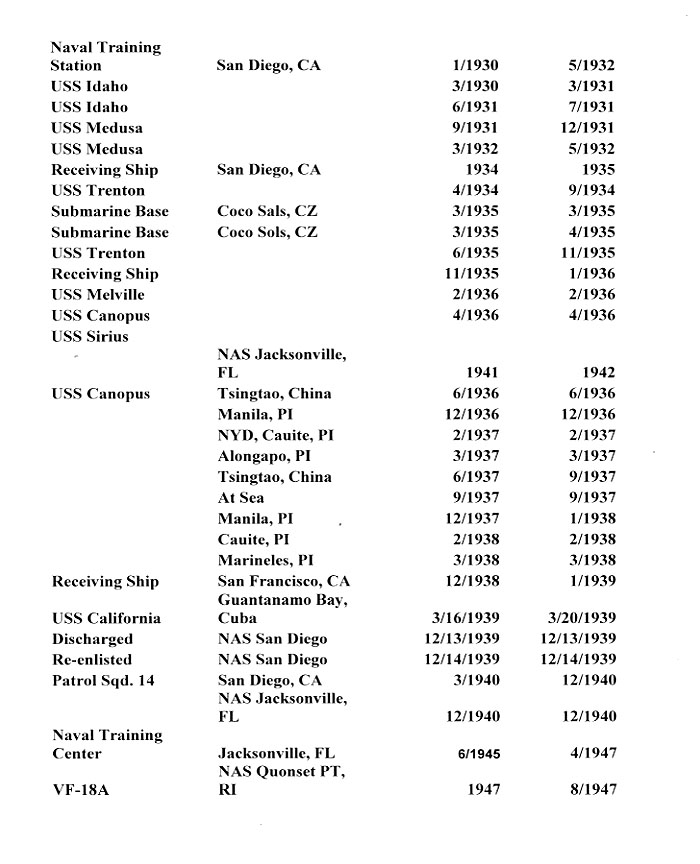

92110

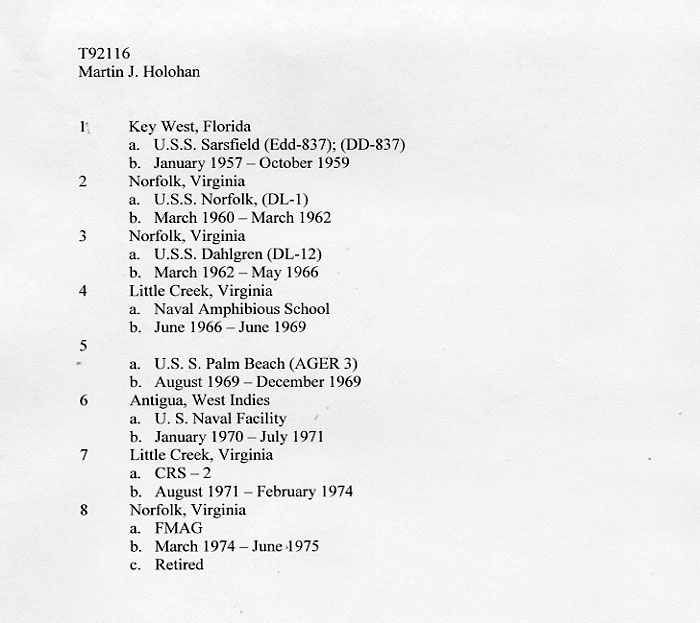

92116

92116  92161

92161  92414

92414

92453

92453  92484

92484  92497

92497

92523

92523  92603

92603  92607

92607  92627

92627

92692

92692

92729

92729  92921

92921  93060

93060  93062

93062  93114

93114

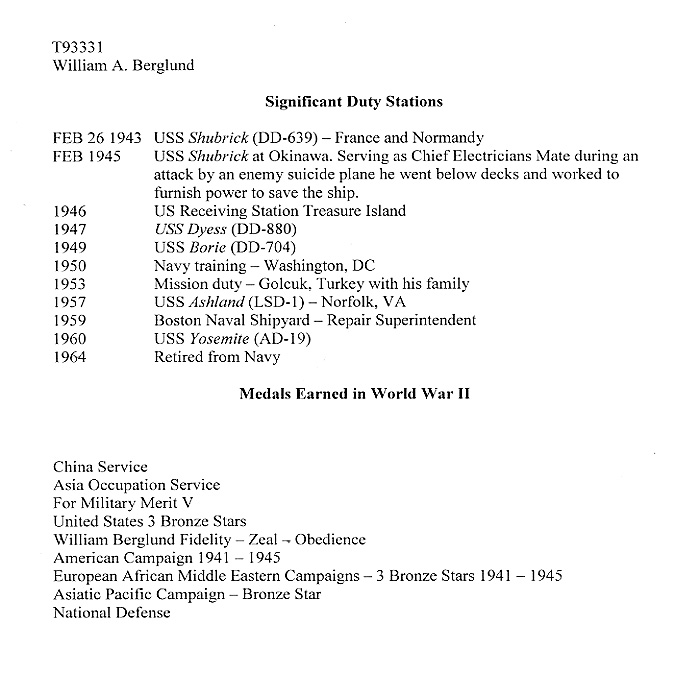

93331

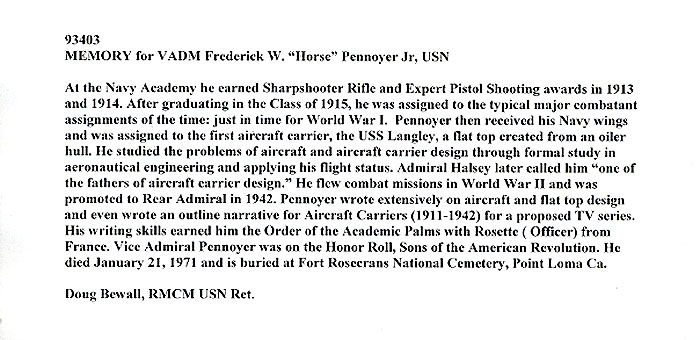

93331  93403

93403  93442

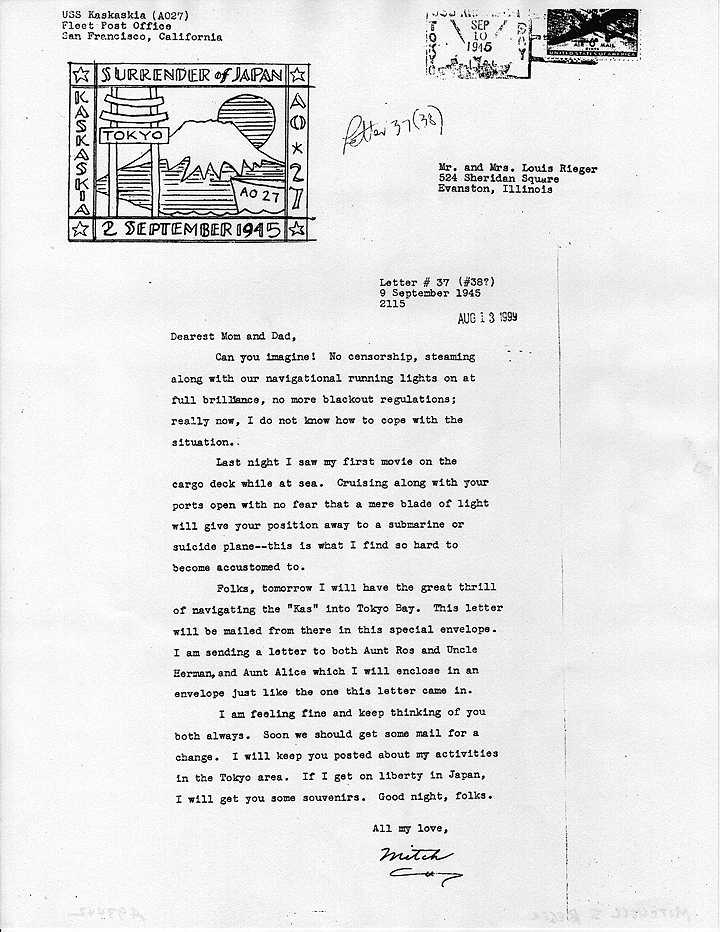

93442  93594

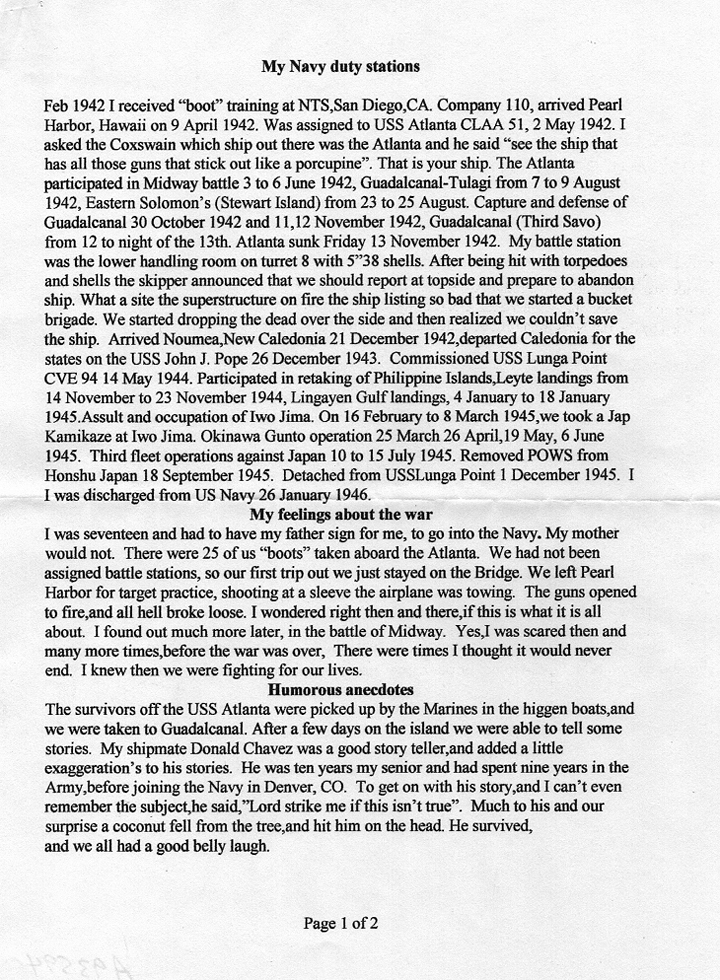

93594

93600

93600  93656

93656

93707

93707  93714

93714  93722

93722  93799

93799  93889

93889

93992

93992  94006

94006

94136

94162

94162

94183

94183

94202

94202  94290

94290

94421

94421  94426

94426  94441

94441

94465

94465

94518

94518  94566

94566  94616

94616

94623

94623

94672

94672  94725

94725  Captain Charles W. Rush, then a lieutenant, is credited with saving USS Billfish (SS 286) and her crew amid depth charge attacks by the Japanese in November 1943. Rush was directly responsible for saving Billfish and directing damage control efforts after the depth charge attack incapacitated the ship's captain and all officers senior to Rush. Keeping calm, Rush was able to sustain the submarine 170 feet below its test depth for 12 hours - with a ruptured aft pressure hull and while the submarine was riddled with major leaks through the stern tubes and various hull fittings.

Captain Charles W. Rush, then a lieutenant, is credited with saving USS Billfish (SS 286) and her crew amid depth charge attacks by the Japanese in November 1943. Rush was directly responsible for saving Billfish and directing damage control efforts after the depth charge attack incapacitated the ship's captain and all officers senior to Rush. Keeping calm, Rush was able to sustain the submarine 170 feet below its test depth for 12 hours - with a ruptured aft pressure hull and while the submarine was riddled with major leaks through the stern tubes and various hull fittings.

After another officer relieved him, Rush discovered the helm was unmanned and that no action had been taken to counter the sustained attacks. He assumed command, found a helmsman and proceeded to direct evasive actions by innovative maneuvers that retraced their path under the submarine's oil slick left by an explosion near the fuel ballast tanks.

Rush eluded the enemy above and surfaced four hours later.

(Source: Navy.mil)

94801

94801  94874

94874  95180

95180  95203

95203

95208

95208  95266

95266  95268

95268  95289

95289  95294

95294  95296

95296

95329

95329

95367

95367  95412

95412

95457

95457

95541

95541  95588

95588

95606

95606  95617

95617  95705

95705

95749

95749  95765

95765

95769

95769 Additional Qualifications:

Enlisted Aircrewman Wings

Surface Warfare Officer Insignia

Engineering Duty Officer Dolphins Insignia

Strategic Deterrent Patrol Pin

95838Flight Hours: 2,383

Carrier Landings: 88

Aircraft Flown: SNJ Texan, T-28B Trojan, TV-2 Training Star, F9F-2 Panther, F9F-6 Cougar, F9F-8 Cougar, FJ-3 Fury, S-2F Tracker, SH-3A Sea Knight

95905

95949

95949  96090

96090

96103

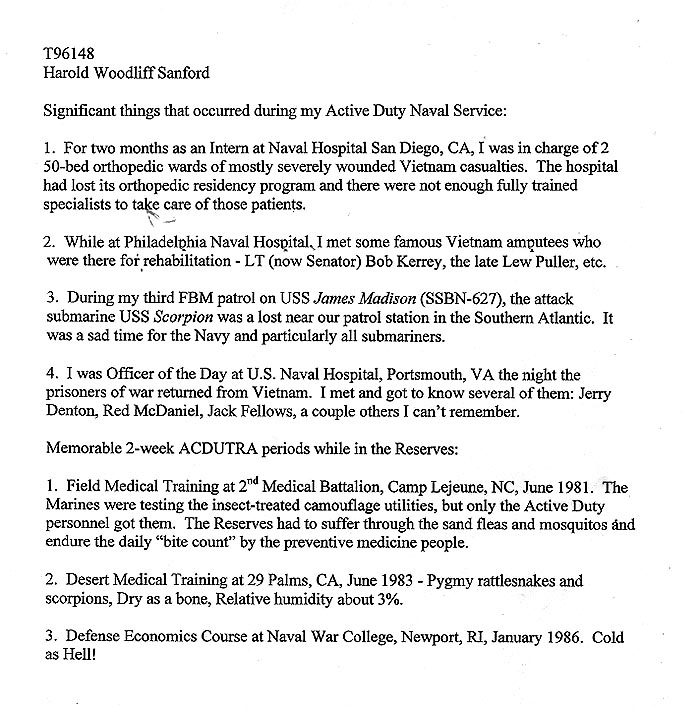

96103  96148

96148  96185

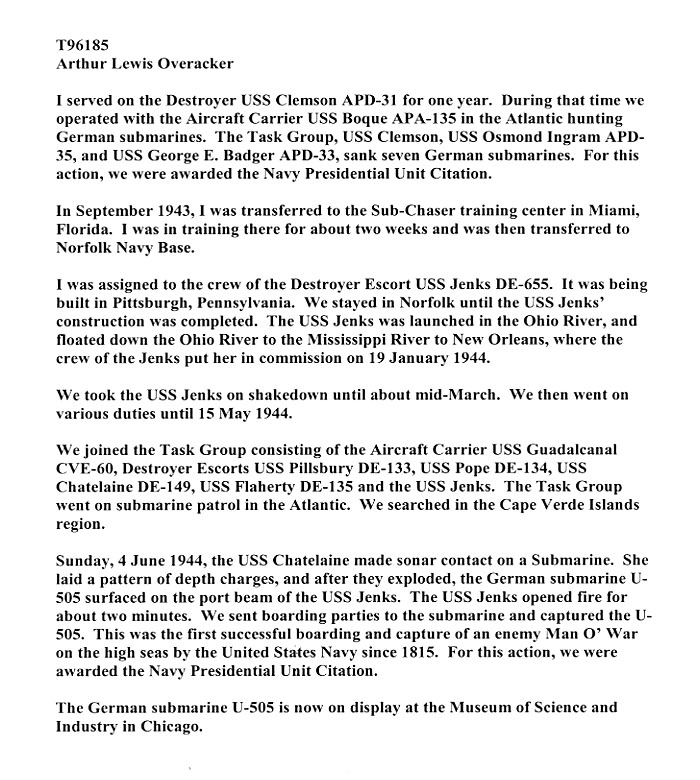

96185  96203

96203  96438

96438  96456

96456

96539

96539  96571

96571

96659

96659  96674

96674

96763

96763  96958

96958  97001

97001 ACDUTAR during OPSAIL '76 and INR 1986 on-board the L.E. Eithne, the Irish ship participating in the review.

Go Navy...Beat Army!

97040 97101

97101  97307

97307

97314

97314  97402

97402

97500

97500

97651

97651  97655

97655

97667 97769

98078

98078  98182

98182  98339

98339  98449

98449

98508

98508  98553

98553  98710

98710  98790

98790

98795

98795

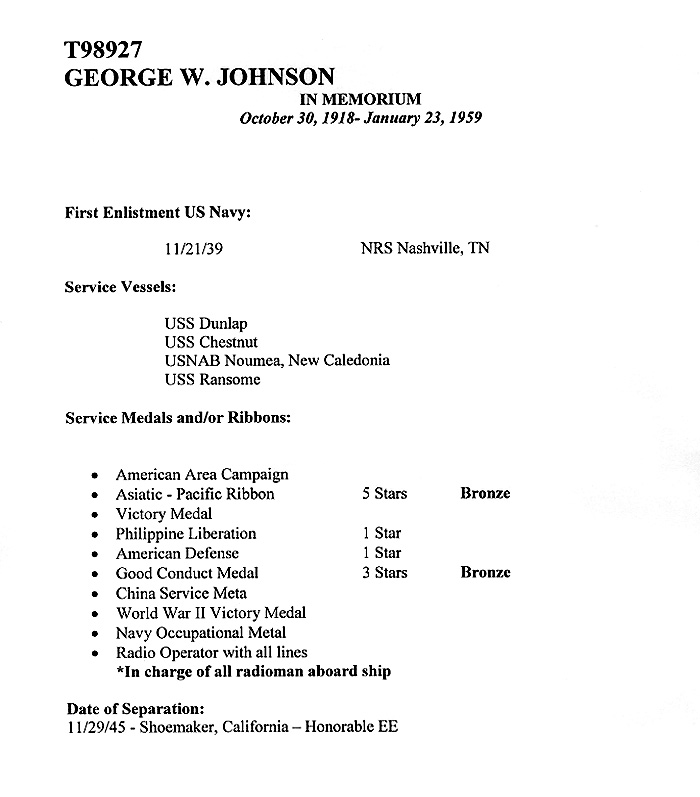

98927

98927

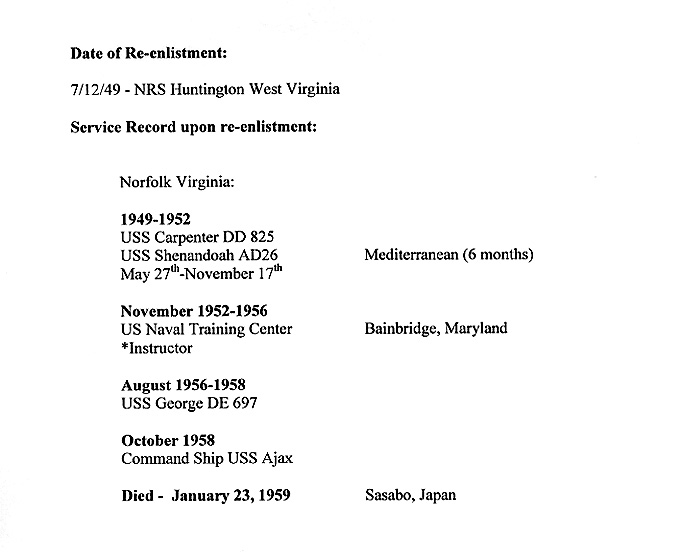

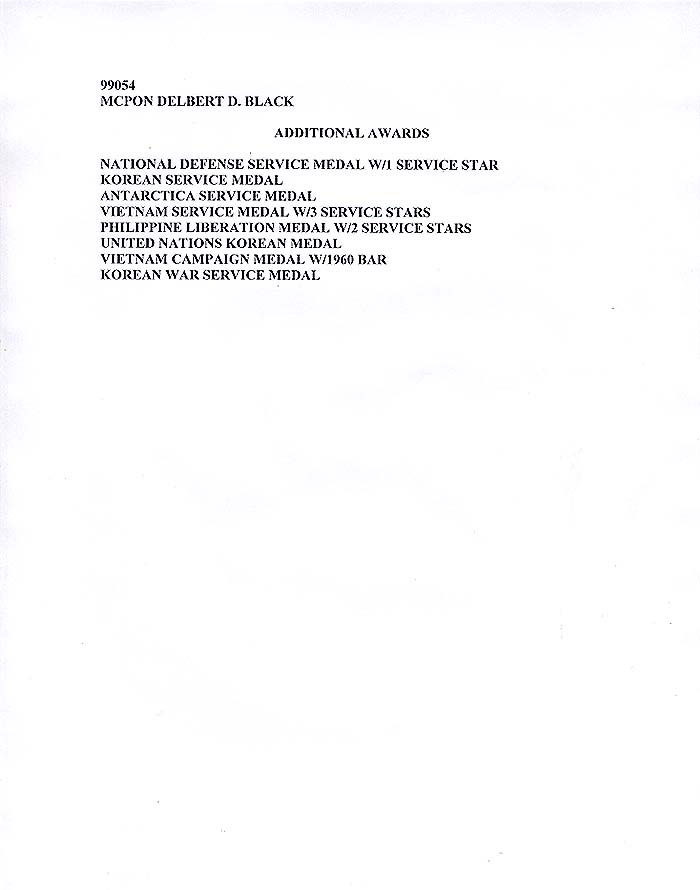

99054

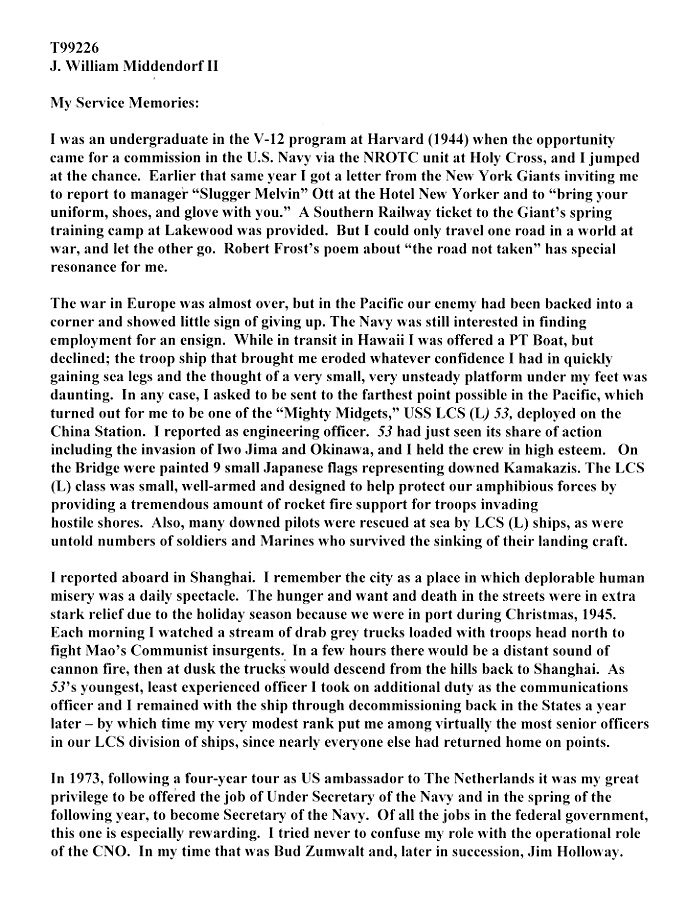

99054  99226

99226

99508

99508  99776

99776  99887

99887  99999

99999

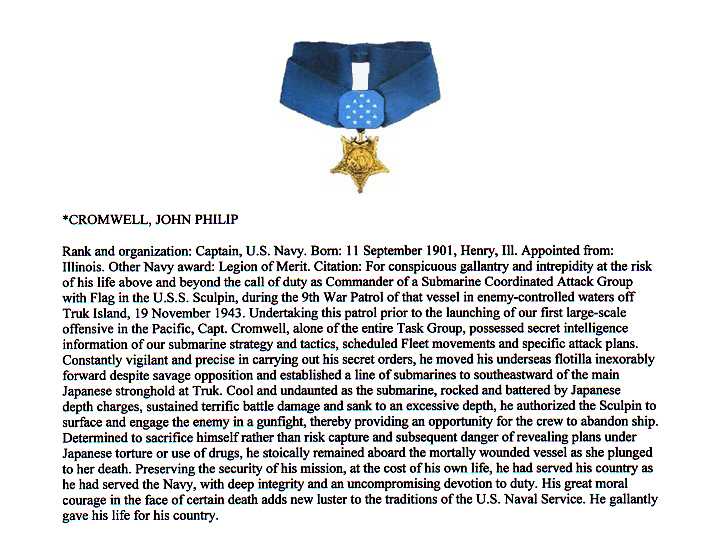

HE CHOSE TO GO DOWN WITH SINKING SUBMARINE

RATHER THAN BECOME A JAPANESE POW

John Philip Cromwell was born on September 11, 1901, in Henry, Illinois, but his heart took him from the Midwest to the ocean. He graduated from the Naval Academy in 1924. His initial sea service was on the battleship USS Maryland but his abilities led to him being picked for the fledgling American submarine force. He served aboard and commanded some of the U.S. Navy's first large submarines. After several tours at sea he was selected for further training in the complex diesel engines that were critical to submarines of that era. He rose through the ranks, eventually becoming a division commander. World War II found now Captain Cromwell in the Pacific commanding Submarine Divisions 203, 43, and 44. His flagship was the USS Sculpin. In November 1943 Sculpin, with Captain Cromwell aboard, put to sea with orders to rendezvous with two other submarines to form a wolf pack to attack Japanese shipping. The Americans were preparing to invade the Gilbert Islands later that month. It would be a critical and bloody fight to wrest control of the central Pacific from Japanese forces. Cromwell was aware of the operation's details and was also familiar with the top-secret American ability to read Japanese military codes.

On November 18, 1943, while en route to the rendezvous, Sculpin’s radar detected a large Japanese convoy and she made an end around at full power to attack the convoy. As Sculpin came up her periscope was detected and the convoy made a turn toward Sculpin so that they would present only a bow to the submarine. After submerging to escape the oncoming convoy Sculpin later resurfaced only to discover that the Japanese destroyer IJN Yamagumo, which had been left behind as a lookout, was waiting only a few hundred yards away. Yamagumo immediately launched a depth charge attack which severely damaged Sculpin. A damaged depth gauge caused her to surface rather than go to periscope depth and she came up directly in front of the Yamagumo, Although Sculpin quickly dived again it was too late. Yamagumo pounded Sculpin with a series of depth charges, causing severe damage. With no way to escape, and more destroyers coming, the Commanding Officer decided to surface again and try to fight it out. Yamagumo was ready. As Sculpin came up Yamagumo's first salvo killed her entire bridge crew including the Commanding Officer and those running to man the weapons. Sculpin's surviving senior officer ordered the submarine scuttled and the crew to abandon ship.

Captain Cromwell, Tactical Commander, was below deck during the battle and realized that if revealed, the secrets he knew could seriously jeopardize the American war effort. He knew the Japanese couldn't be allowed to learn the invasion plans or that the Americans had broken the Japanese codes. While he knew he wouldn't voluntarily talk he felt there was no guaranteeing he might not break under torture or the influence of interrogation drugs. He therefore decided to stay with Sculpin forever to insure the enemy could not gain any of the information he possessed. He helped the crew abandon ship but made no move to leave himself. He was last seen standing in the control room watching it fill with water.

For his heroism and devotion to country he was posthumously awarded the Medal of Honor. It was presented to his widow.

Submitted by CDR Roy A Mosteller, USNR (Ret)

100159 100290

100290  100685

100685

100712

100712

100751

100751  100821

100821  100970

100970  101223

101223  101434

101434  101467

101467  101636

101636

101666

101666

101862

101862  101942

101942

102020

102020  102036

102036  102042

102042  102447

102447  102590

102590  102652

102652 Duty Stations

Aug 64 - Nov 65 United States Navy and Marine Corps

Reserve Center, Cincinnati, Ohio

Dec 64 - Jan 65 Recruit Training Command, Great Lakes

Jul 65 - Aug 65 USS BRISTOL (DD-857)

Nov 65 - Jan 66 Naval Station, Norfolk

Jan 66 - Jan 67 Fleet SONAR School, Key West

Jan 67 - Jun 67 Fleet Anti-Submarine Warfare School, San Diego

Jul 67 - Jun 68 USS LUCE (DLG-7), Mayport

Jun 68 - Mar 70 USS GLENNON (DD-840), Newport

Mar 70 - May 72 USS MACDONOUGH (DLG-8), Charleston

May 72 - Jun 72 Fleet Training Center, Norfolk

Jun 72 - Jun 75 Recruit Training Command, Orlando

Jul 75 - Sep 75 Fleet Anti-Submarine Warfare School, San Diego

Oct 75 - Mar 80 USS LUCE (DDG-38), Mayport

Mar 80 - May 80 Navy Recruiting Orientation Unit, Naval Training

Center, Orlando

May 80 - May 83 Naval Recruiting District, New York City

May 83 - Jun 83 Career Counselor School, Norfolk

Jun 83 - Jun 87 Naval Surface Group FOUR, Newport

May 86 - Jul 86 Senior Enlisted Academy, Class 22 Green, Newport

Jun 87 - Oct 90 Senior Enlisted Academy, Newport

Nov 90 - Dec 93 USS SARATOGA (CV-60), Mayport

Dec 93 - Feb 96 Strike-Fighter Wing, Cecil Field, Jacksonville

On January 31, 1942, William left his home in Cincinnati, went across the Ohio River to Fort Thomas, Kentucky, lied about his age and enlisted in the U.S. Army. He was only 15 years old. He was assigned to the 4th Armored Division, 37th Armored Regiment, at Camp Bowie, Texas. Because he was underage, after serving about 15 months, he received an Honorable Discharge on August 24, 1943.

On June 9, 1944, he enlisted in the U.S. Navy. He saw action in the Pacific aboard the USS IBEX (IX 119) and the USS BREMERTON (CA 130). After the war, he was honorably discharged as a Seaman First Class, under the points system, on February 25, 1946.

102721

102767

102767  102869

102869 102869

Richard Wayne Gillette

Richard was born on 15 May 1950 in Coronado,

Dependent, he traveled around the

an excellent student and always wanted more knowledge. He spoke

several languages besides English: e.g., French, Spanish, and German.

He graduated from

He then attended the

to the states and graduating from the

Commanding Officer of NISO

of Boot Camp, he went to

the Enlisted

he was assigned to duty on the USS BILLFISH (SSN-676). Upon

completion of his enlistment, he received an Honorable Discharge,

and once again went traveling. He worked on a Kibbutz in

and then went to

accident on 5 May 1981. He is now interred for his final rest at Brevard

Halbert Gillette Dorothy Gillette

#00717216H

103036

103199

103199

103212

103212  103360

103360  103365

103365

103371

103371 LEARNING TO LAND ON A CARRIER

Then ENS Robert E. Holmbeck was a fledgling dive-bomber pilot who logged 300 hours in Helldivers in less than a year. In late 1944 his operational training unit, based at Cecil Field, in Jacksonville, Florida, flew SBW-3s and SBT-3, after which he joined the VB-97 pool at NAS Grosse Ile, Michigan, which was equipped with SB2C-4s. In an article published in the September 2003 issue of SCUTTLEBUTT, the newsletter of the USS Guadalcanal Task Group 22.3 Association, he described some of his evolution into being a qualified fleet-ready bomber pilot:

After 10 to 15 hours of field carrier landing practice we became comfortable with flying low at slow speed. Then we went out to a carrier standing by at sea to become full-fledged carrier pilots. Our ship was USS GUADALCANAL (CVE-60), out of Mayport, Florida. It was a small escort carrier that couldn't take many aircraft at one time, so we flew out with six '3Cs, each with another pilot in the back seat to conserve deck space. Sitting in the back seat as we approached the deck I remember looking at that little CVE wondering, How does anyone get aboard that? Unbelievable that in this big, wide ocean, there was such a small rectangular piece of deck that we had to get that big airplane onto! The pilot made the landing, the crew chocked the airplane with the engine still running, and I jumped in the front seat for my first takeoff. No problem. I went around - everything was fine. On the downwind leg at 200ft altitude I did the checklist - mixture rich, prop low pitch, gear, flaps and hook down. Coming abreast of the stern I came around on base leg and picked up the LSO's paddles. Now I'm focused on him all the way in - too low, slow, high, fast, whatever. When he gave the cut, I chopped the throttle and pushed over to head right for the deck, then came hard back on the stick so that the airplane would plop down in a three point attitude. The airplane snagged a wire right where it was supposed to. Man! My confidence level went up about 1000 percent. From then on it's a piece of cake, or so I thought!

After three or four landings with things going very naturally, I came up the groove and everything was normal. The carrier was at a small angle to the wind, not straight down the center. That day it was 10 to 15 degrees right so prop wash was going off to the left. Receiving the cut signal from the LSO I pulled back on the throttle, heading for the deck. While coming back on the stick I noticed that the aircraft was drifting left. I was not down the centerline of the deck. In that fraction of a second I saw things were not as they should be. When I plopped down I opened the throttle, still drifting off the deck. Somehow the tail hook bounced between two arresting wires failing to catch a wire, or I'd have been in big trouble. And though the wing missed the catwalk, I was headed for the drink. I hauled back on the stick, the throttle was wide open, and this thing was settling, settling, settling. It looked to me like I was going in the water but the machine hung itself on the prop. It didn't settle any further, so I got the gear up and hung on for dear life. I don't know how long it took me to get some decent flying speed but I got going again, rejoined the pattern and continued on. You couldn't come any closer to going in the drink but luck was on my side. I made the next landing with no problem and finished the required number but I often wondered why I didn't get wet. Sometime later I looked back in my logbook and I got a little upset. For some reason the damn fools didn't even give me credit for a 'touch and go' landing!

Contributed by Bob Holmbeck, TG22.3 Association Member

Subsequently Holmbeck received orders to VB-4, the Tophatters, at NAS Wildwood, New Jersey, with SB2C-5s and was then assigned to the brand new Essex Class carrier, USS TARAWA (CV-40) for her first deployment in the Western Pacific.

Submitted by CDR Roy A. Mosteller, USNR (Ret)

103515

103555

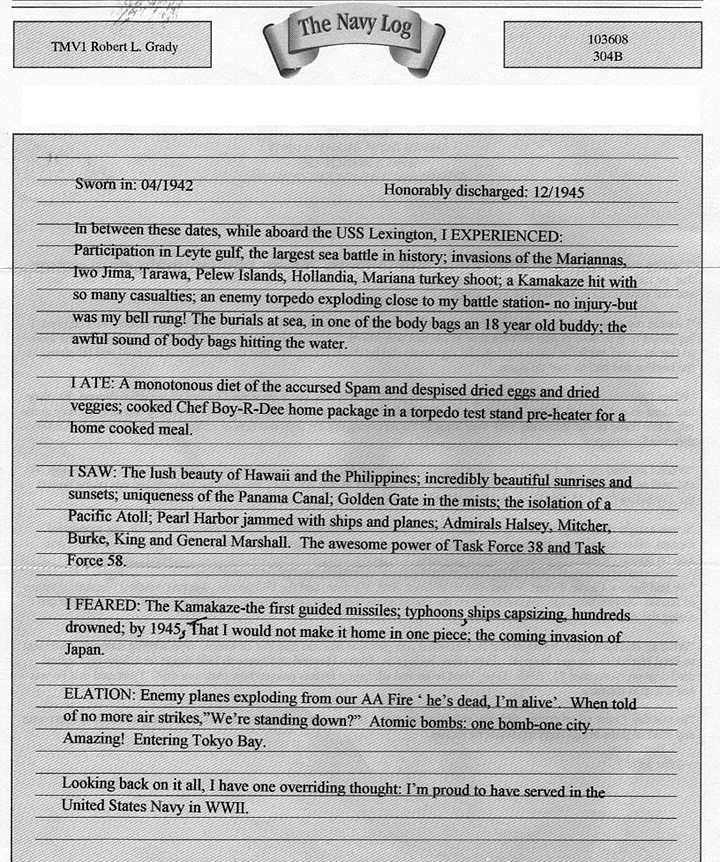

103555  103608

103608  103637

103637

103689

103689  103738

103738  103819

103819  103822

103822  103867

103867  103971

103971

103980

103980  104200

104200  104209

104209

104310

104310  104469

104469

104543

104543

104646

104646 Heywood Lane Edwards was born at San Saba, Texas, 9 November 1905 and was graduated from the Naval Academy in 1926.

After serving in battleship Florida, cruiser Reno and other ships, he underwent submarine instruction in 1931, served in several submarines, and was assigned to cruiser Detroit in 1935.

On 6 April 1942, LCdr. Edwards assumed command of Reuben James, which in March 1941 joined the convoy escort force established to ensure the safe arrival of war materials to Britain.

On 23 October 1941, the “Rube” sailed from Argentia, Newfoundland in the escort of convoy HX-156. At about 0525 on 31 October, she was torpedoed by German submarine U-562. Her magazine exploded, and she sank quickly. Of the crew, 44 survived but 115 were lost, including LCdr. Edwards.

Submitted by Doug Bewall RMCM USN Ret.

104674 104921

104921  104925

104925  104966

104966  105126

105126  105336

105336

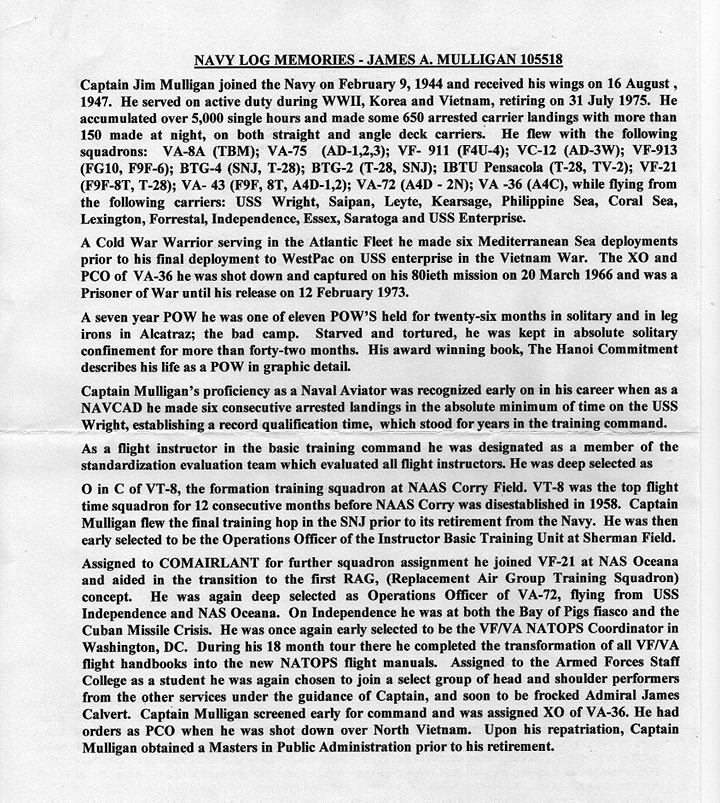

105518

105518

105575

105575

105584

105584

105633

105633

105712

105712

MOST DECORATED ENLISTED MAN IN NAVY HISTORY

James Elliott Williams, a Native American Cherokee from South Carolina, entered the Navy in July 1947 and before retiring in April 1967 gained the distinction of becoming the most decorated enlisted man in Navy history. When he retired from active service he was employed with the Wackenhut Corporation and in 1969 was appointed to the U.S. Marshal Service in South Carolina. He also became an instructor at the Federal Law Enforcement Training Center, Glynco, Georgia, and also served at the U.S. Marshal Service Headquarters in Washington, D.C., until his retirement from Federal Government Service.

Williams died on October 13, 1999, and was buried at Florence National Cemetery in Florence, South Carolina. The Master Chief Petty Officer of the Navy, speaking at the funeral said, “We will forever be grateful for the leadership and commitment he showed his sailors. Petty Officer Williams was an amazing sailor.” Following his death a retired Rear Admiral who commanded Williams in Vietnam remarked, “Willie did not seek awards. He did not covet getting them. We did not seek to make him a hero. The circumstances of time and place, and the enemy’s presence did that. I know through personal investigation of each incident that he never placed his crew nor his patrol boats in danger without first ensuring the risk was calculated and that surprise was on his side. He always had the presence of mind not to endanger friendly villages. He inspired us all, junior and senior alike. It was my greatest honor to have served with the man who truly led us all with his example of unselfish devotion to duty.” In December 2004 the USS JAMES E. WILLIAMS (DDG-95) was commissioned in his honor.

ALL HANDS MAGAZINE - JULY 1998

Boatswain's Mate 1st Class James Elliott Williams never intended to be a hero -- he just wanted to be a Sailor. "When I was 16, I convinced the county clerk to alter my birth certificate so I could come into the Navy. I thought there was nothing better than servin' my country and gettin' paid for it.” But, Williams first experience at sea was less than glorious. In fact, it was downright boring. "The first ship I drew, I was the most disappointed man in the world. I'd joined the Navy to see the world -- and doggonit, I wasn't moving. I'd got orders to an LST that just sat around a buoy in San Diego harbor." But, from that experience, Williams learned a valuable lesson about discipline and leadership. "An old chief told me, 'Son, you got to learn to take orders, even if you disagree with them. That's the first step to being a good sailor and a good leader. If you can't take orders now, you certainly won't be respected when you give them later.' Well, I got the message. Learning discipline was the springboard that helped my Navy career. From then on I had the sharpest damn knife and the shiniest shoes in the Navy. That's what I was taught. That's what I believed in, being a good Sailor. The proudest day of my life had nothing to do with medals, ribbons, citations. It was when they made me a patrol officer. That position was held only by chiefs and officers. It showed the trust the Navy had placed in me. I always wanted the opportunity to show what I could do. This Vietnam thing was it for me. The Navy gave me the chance to do my job."