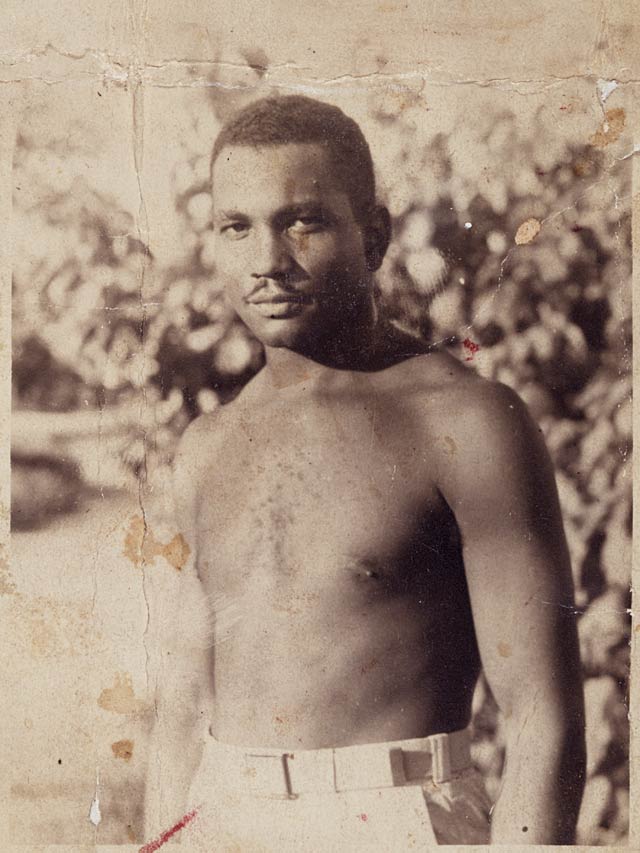

RUSHTON-WILLIE

WILLIE HERD RUSHTON

PFC

A MONTFORD POINT MARINE

In 1942 President Roosevelt issued a presidential directive giving African Americans an opportunity to be recruited into the Marine Corps, that they were permitted to serve. Even then African Americans were not permitted to join traditional units but were segregated.

Willie Herd Rushton was born on July 14, 1920, in Nadawah, Alabama, a town so small it is not on most maps. His grandfather, who had been reared in Montgomery, was born a slave. Willie grew up on a saw mill farm in Atmore, graduated from high school in 1941, and moved to Mobile where he got a job at the Coca-Cola Bottling Plant. He got married in 1942 and was drafted in the spring of 1943. When given the opportunity to choose his service, Willie chose the Marine Corps, later saying, “My mother and father, they always told me whatever you be, be the best.”

Following basic training at Montford Point, Camp Lejeune, North Carolina, he shipped out for the Pacific in July 1943 as a member of the 11th Depot Company, 1st Marine Division. The company’s assignment was simply to serve as stevedores, loading and unloading supplies away from any fighting. Willie Rushton later said:

“Sometimes I’d be lying up there in my tent at night and say, ‘I wonder, did I do the right thing? Wonder if I’ll ever get the chance to see my son.’ (His son was born 2 months after he was sent overseas.) And then I’d say, ‘Well, one thing about it, they can always tell him that I was over here trying to make a better place for him to live in the United States.’ So then I stopped worrying about that. I said, ‘I’m over here to make things better. That’s what I’m doing over here.’”

Willie Rushton soon found himself in the thick of the fighting on Peleliu. Although he had petitioned before landing on Peleliu to be allowed to fight, his company was told they would only carry supplies to the front and carry back wounded marines. In the end, there was little room for such fine distinctions. “We were right there where the fighting was going on,” Rushton recalled. “They was just knocking us off, and we came forward. It didn’t make no difference whether you was black or white or whatever. They didn’t care when you got into combat.” A number of Rushton’s company were hit and Rushton was one of them when he was wounded by shrapnel from a Japanese mortar. He was carried to a hospital ship offshore, the only wounded black man aboard. After his wounds were treated, he asked if he could have a haircut. The ship’s barber refused.

“He told me, said, ‘I can’t cut your hair.’ So, a couple of white marines asked him, said, ‘Why can’t you cut his hair? You don’t have to give him no style, just cut his hair off. All he wants is some of that hair off his head.’ So he said, ‘No. I can’t cut his hair.’ Then the captain of the ship came down there and told that barber, said, ‘I’m telling you for the first and the last time. I don’t care who comes on this ship, if he’s an American soldier, whether he’s black or white, or whatever, I want you to cut his hair, you know, just cut his hair.’ He said, ‘Don’t ever make a remark like that anymore.’”

Willie Rushton got his haircut. He was discharged from the Marines in November 1945 and returned to Mobile. He was unable to reclaim his old job at the bottling plant but he eventually found work at Sears and then at the U.S. Postal Service, where he stayed for 43 years and was affectionately referred to as “The Chief.” Willie Herd Rushton died on September 21, 2008, and following a service with full military honors, was interred at Serenity Memorial Gardens in Theodore, Alabama. His memorial marker carries the inscription: PFC - US MARINE CORPS - WORLD WAR II - PURPLE HEART

Submitted by CDR Roy A. Mosteller, USNR (Ret)